By Hassan I. Conteh

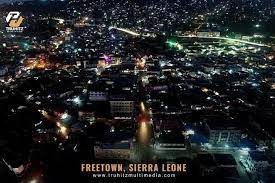

There is this old-aged, cherished, sweet saying in a popular musical chorus that: “Home, home sweet home; no place like home.”

Indeed, you will not know how true is this statement until you leave your country to live in a foreign land.

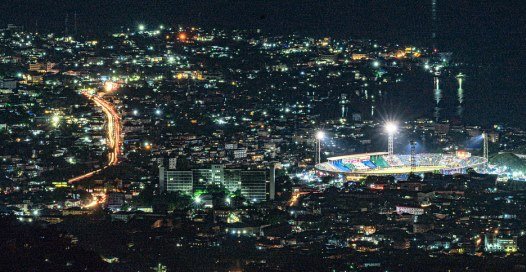

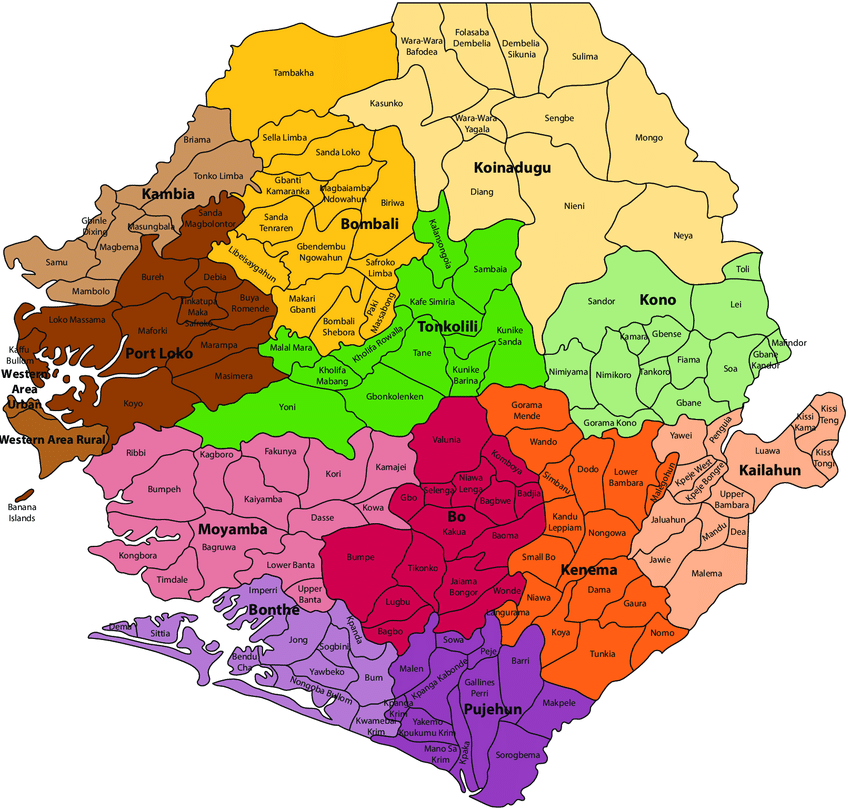

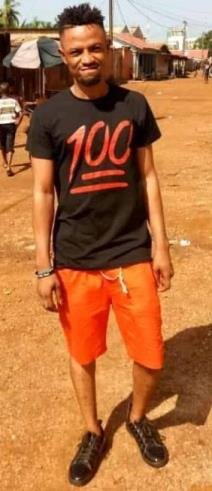

A Sierra Leonean who has travelled extensively around the globe is among hundreds of Sierra Leoneans who have shared their experiences with fellow home-based Sierra Leoneans after the diasporas have stayed up in abroad for a number of years.

Almost all their experiences shared have deep commonality, believing that one’s home country is sweet like one is drinking water.

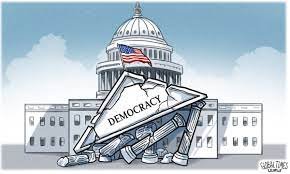

The sweetness is the freedom one gets to enjoy. It’s the key asset one misses when one lives in another man’s country.

“You’ll never know how value your country is until you are in another country.

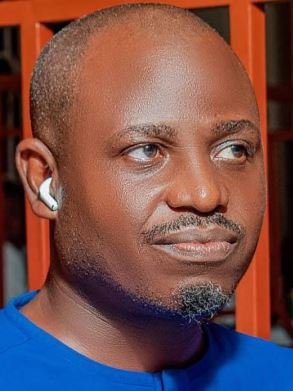

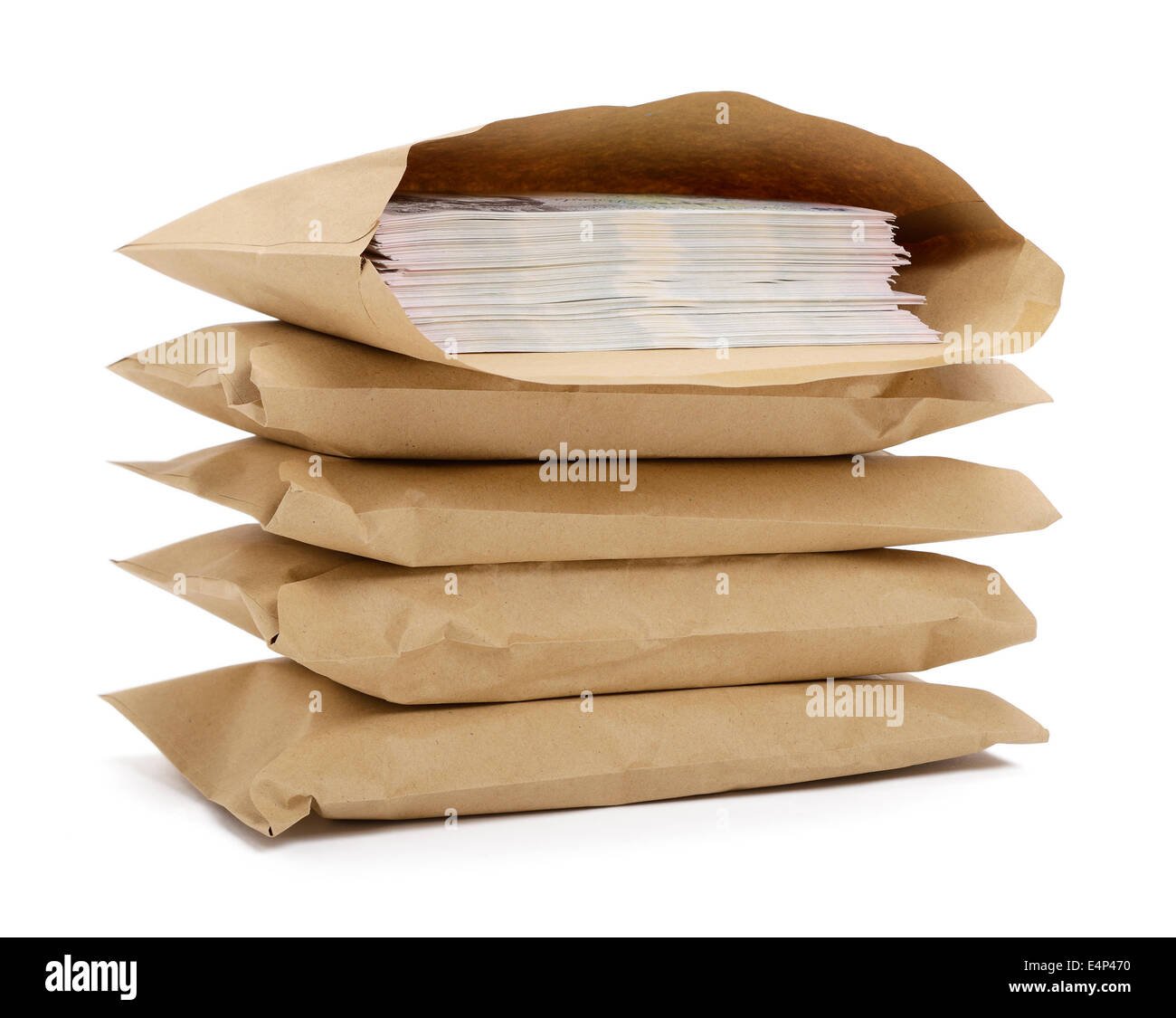

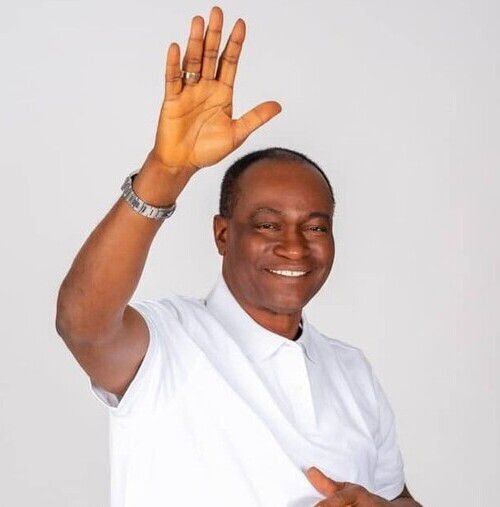

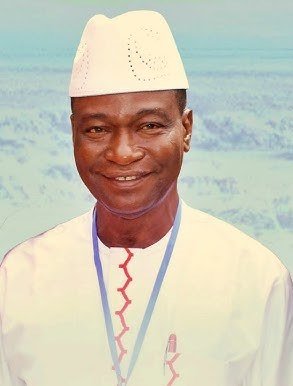

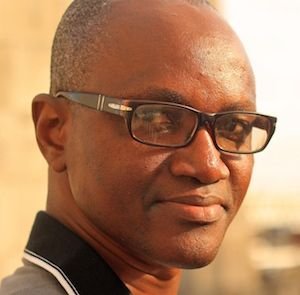

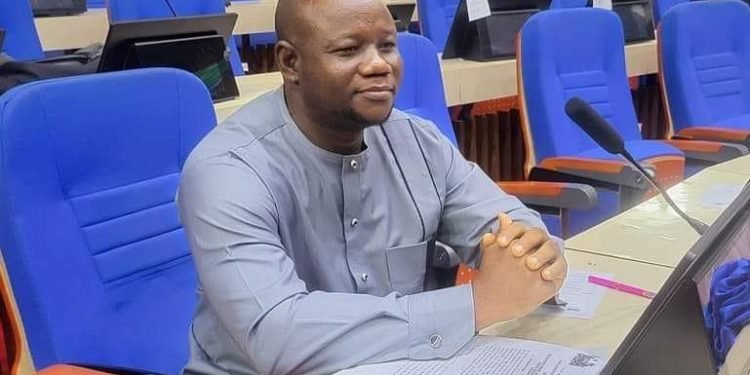

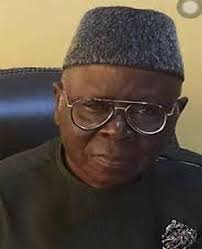

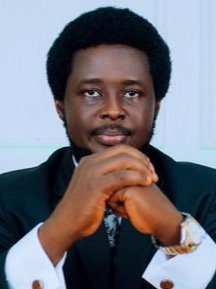

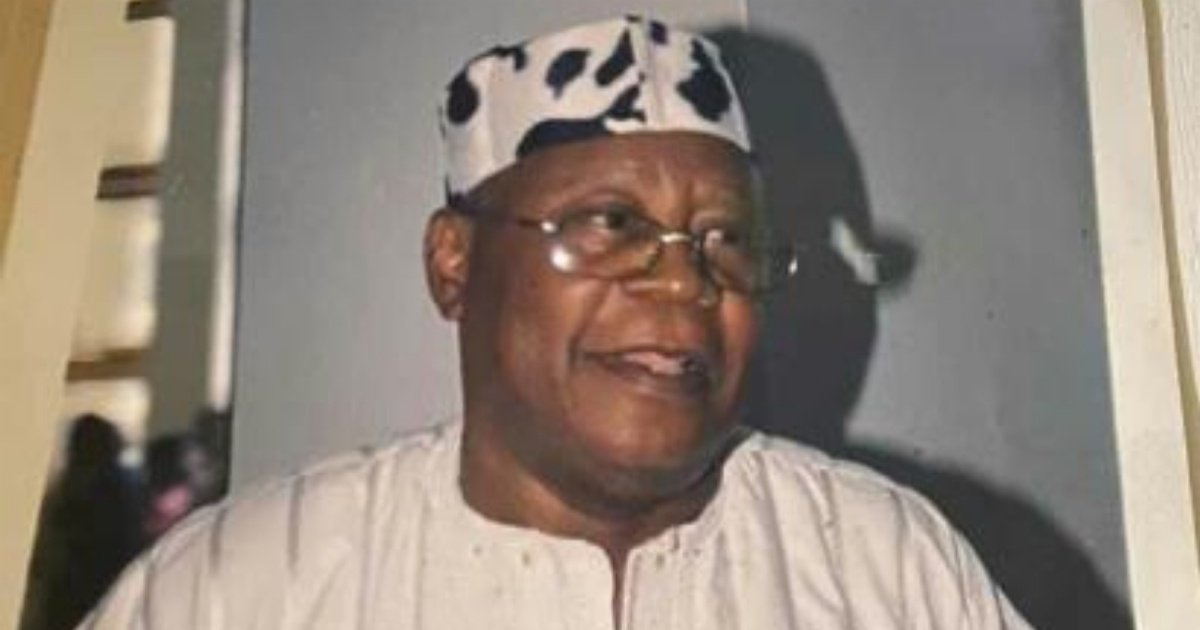

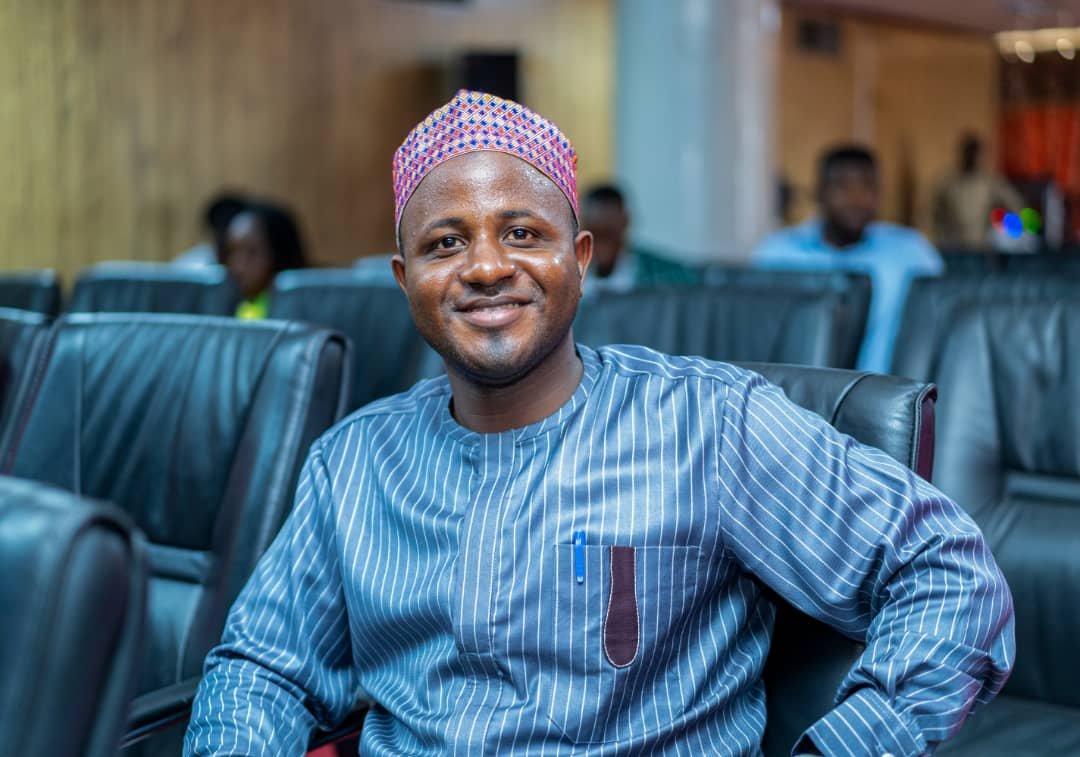

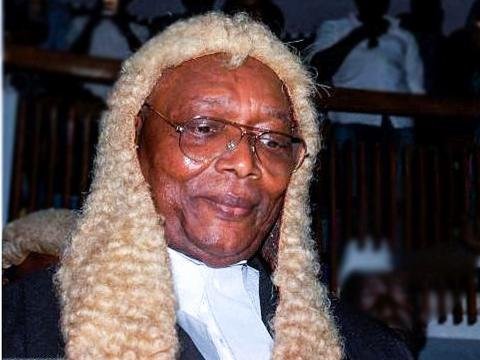

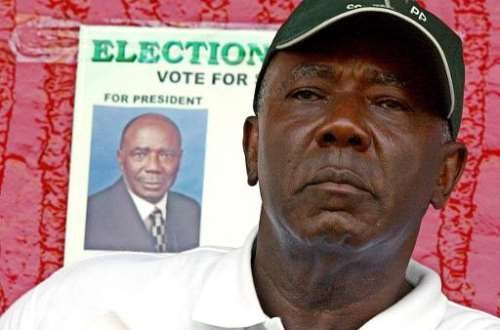

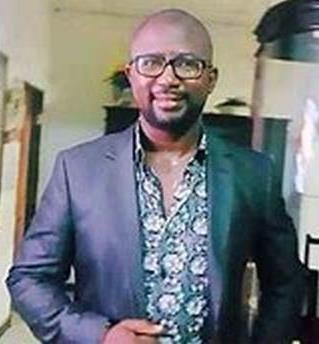

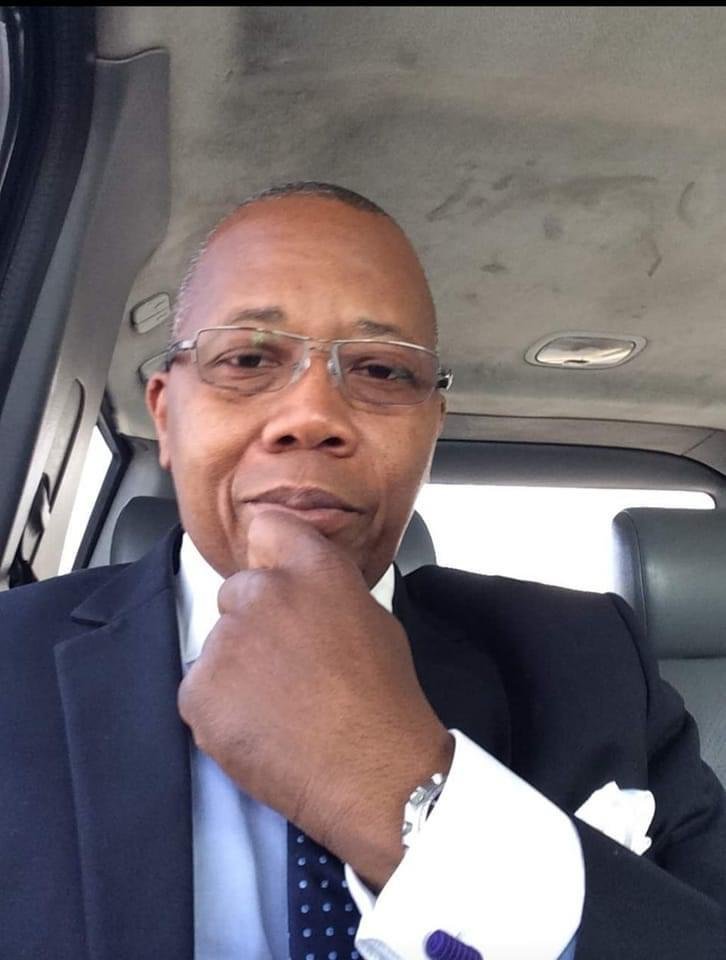

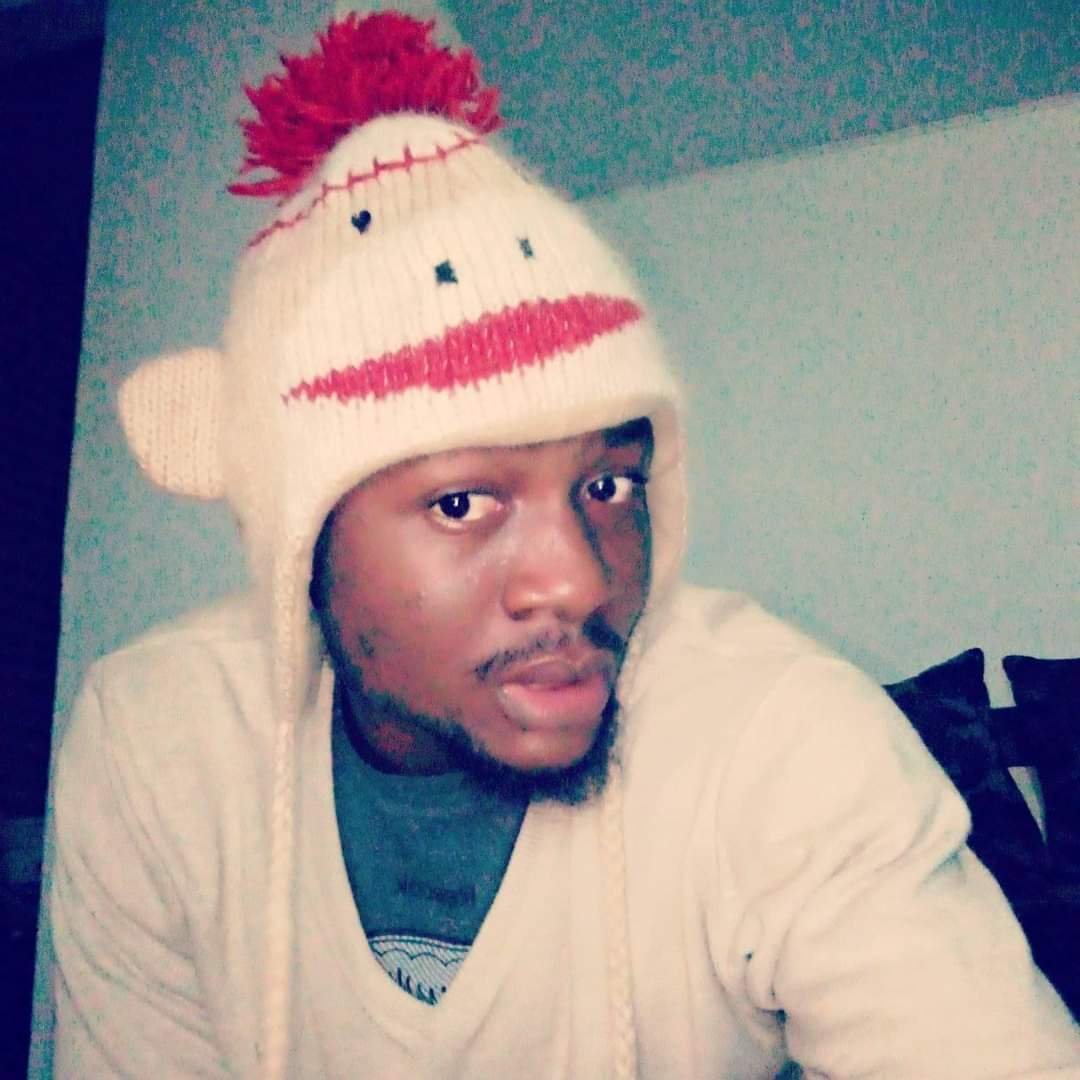

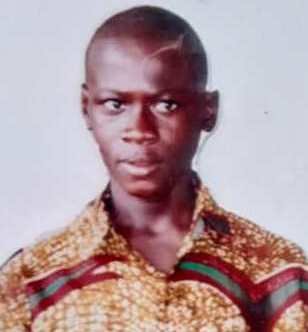

You almost get asked anywhere for [documents] such as residence permit whenever you’re caught up in the street,” says Sheik Ibrahim, who is well-known as Sheik Libya in his community in Freetown.

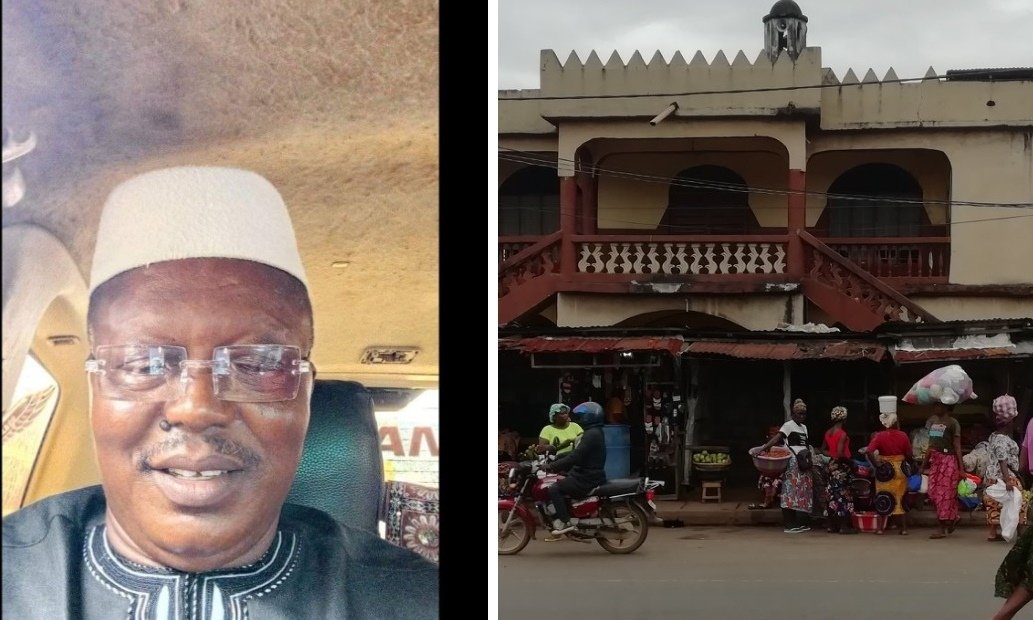

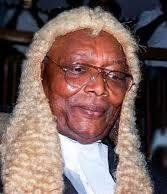

He’s an Islamic scholar and principal at Islamic Dawah Institute (Harakah) at Qarry, Bai Bureh Road, east of Freetown.

“When you live in your country, you get enough Freedom; you don’t get asked by people for simply visiting important places like museum, seaport, etc.

“For me, I often feel good to go on a long stroll to important places while I was in some European countries and Arabian countries; you get to learn a lot more by doing do. So while I was in those countries the liking to going out visiting places were my pastimes.”

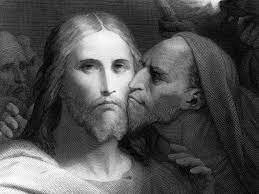

However, Sheik Ibrahim Khalil, had had a tragic incident while he was in Libya studying during 2011 Arab Uprising.

“I almost got myself locked up in jail when I attempted to free up a Nigerian’s friend’s wife [a Sierra Leonean woman] who was about to be sent in prison herself because she hadn’t a marriage certificate.

“Since I was student union head, I had to help that woman and her Nigerian husband by securing her a marriage certificate through our embassy and by travelling to where she was in Bengazi to free her up. But I had difficulties at first; I was refused to let her out and almost got myself locked up in jail even though I presented all my credentials as student but they could trust me – the revolutionists – probably, soldiers.

“It was only when they saw me praying Asr that they said to themselves: Oh! he is a Muslim; let him go along with that woman,” the scholar explained his sad experience.