Abstract

This article examines the interpretative authority of the Speaker of Parliament in Sierra Leone, focusing on a ruling regarding the prepositional phrases “in Parliament” and “of Parliament” during the removal proceedings of Auditor General Lara Taylor-Pearce. By analyzing linguistic, legal, and procedural dimensions, the article explores how constitutional language shapes governance outcomes within Commonwealth parliamentary traditions (Erskine May, 2023).

The Speaker’s interpretation of these prepositions, grounded in Section 137(7) (b) of the Constitution of Sierra Leone (Act No. 6) of 1991, facilitated a procedurally compliant resolution to a complex constitutional question (House of Parliament of Sierra Leone, 2023). While some commentators argue that alternative interpretations were possible, the ruling underscores Parliament’s role in adjudicating constitutional questions relatable to its proceedings.

Introduction

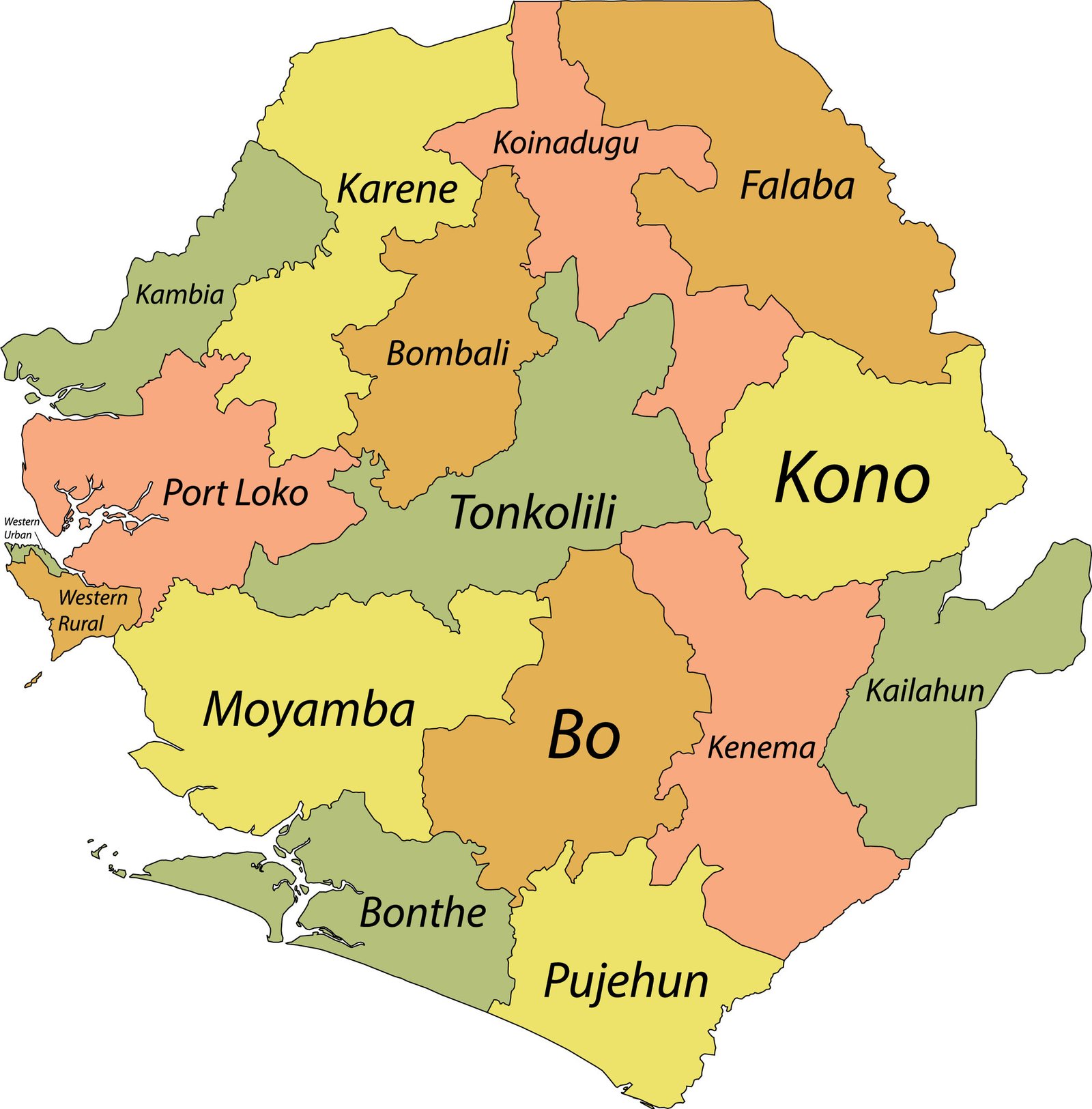

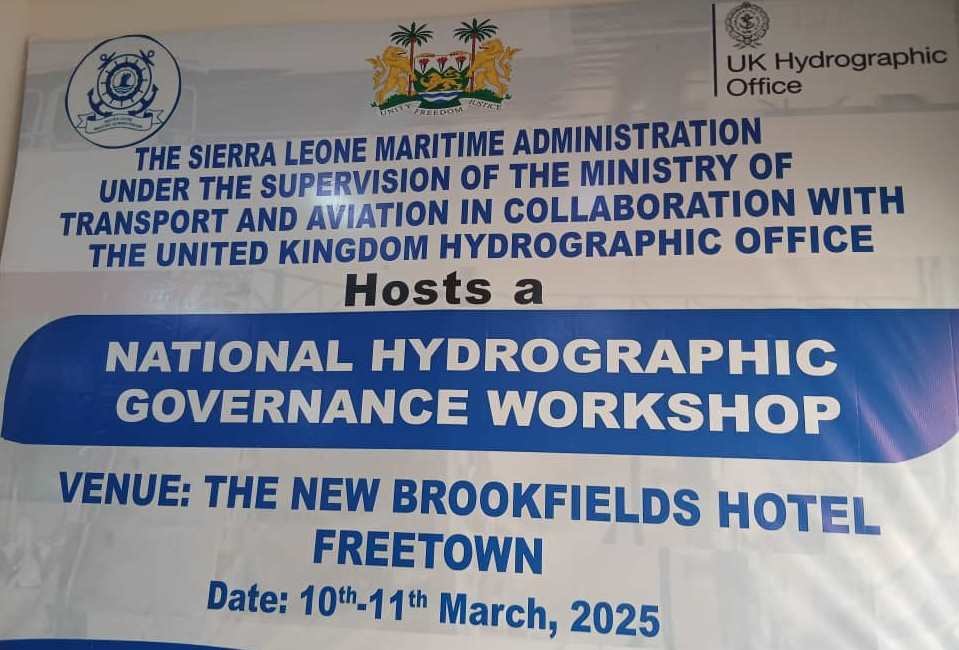

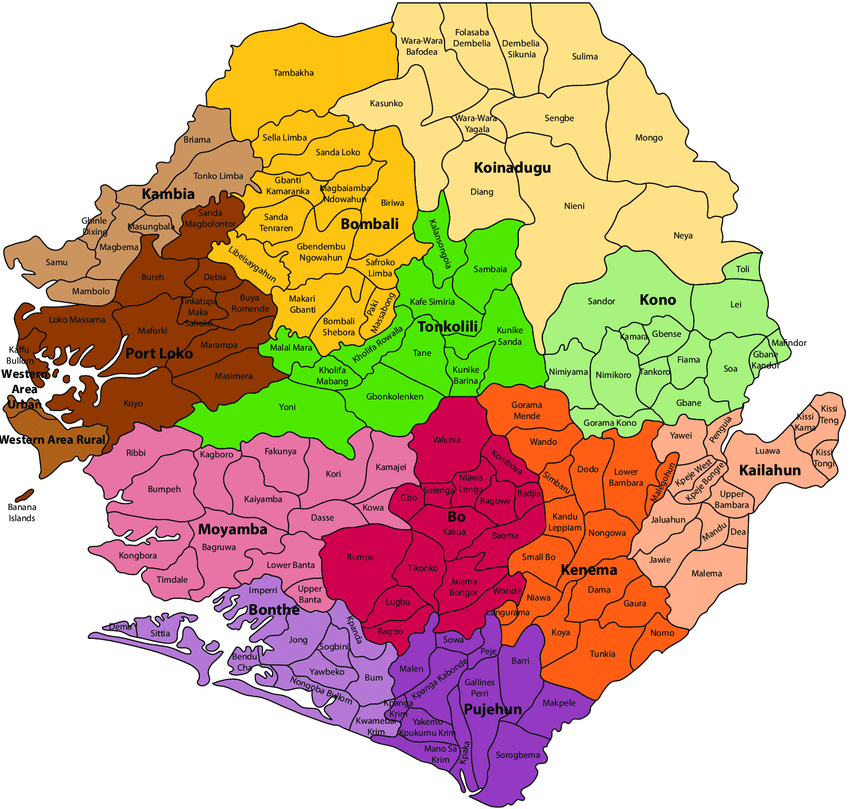

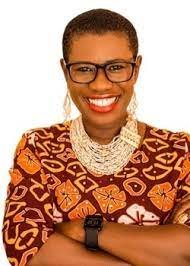

The removal of Sierra Leone’s Auditor General in December 2024 brought renewed attention to the constitutional role of Parliament in overseeing independent offices. Central to the proceedings was the Speaker’s interpretation of the phrase “two-thirds majority in Parliament” under Section 137(7)(b) of the Constitution (Constitution of Sierra Leone, 1991). This case highlights the ongoing challenge of balancing procedural clarity with constitutional intent, a recurring issue in Commonwealth parliamentary practice (Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, 2021). Rather than viewing the ruling as politically motivated, this article focuses on the procedural and jurilinguistic complexities inherent in constitutional interpretation, particularly in a parliamentary setting.

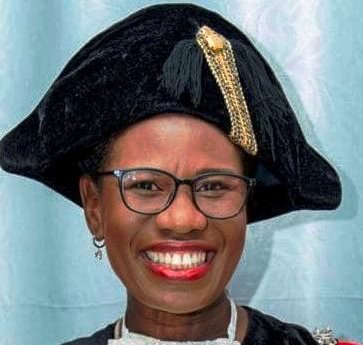

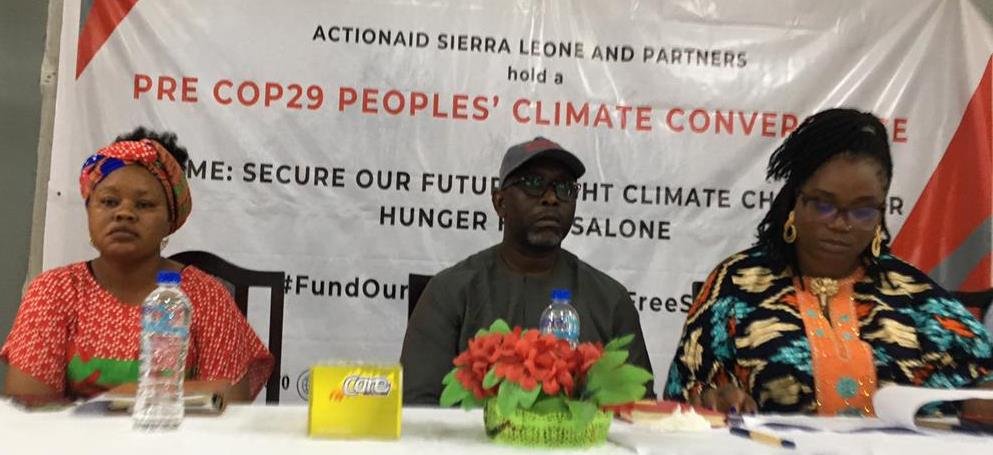

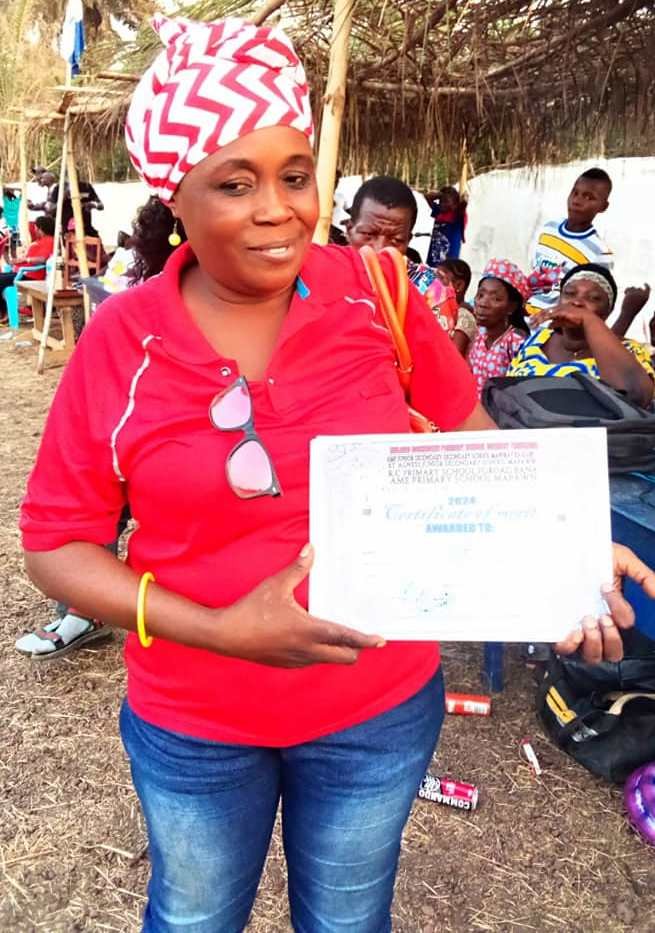

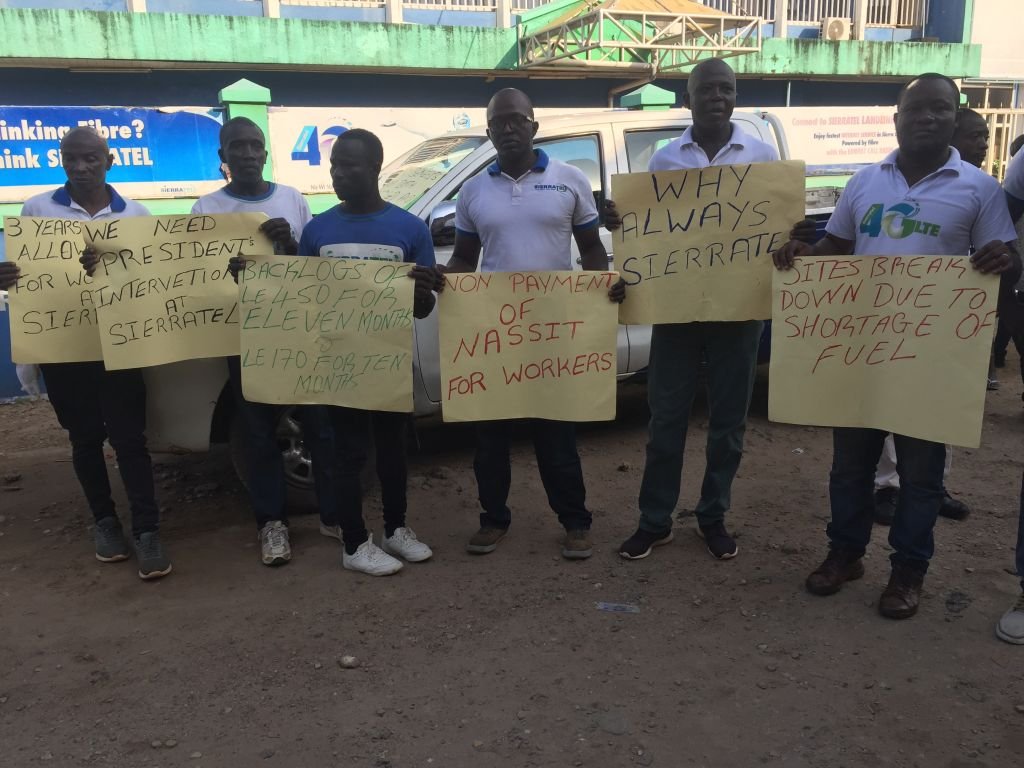

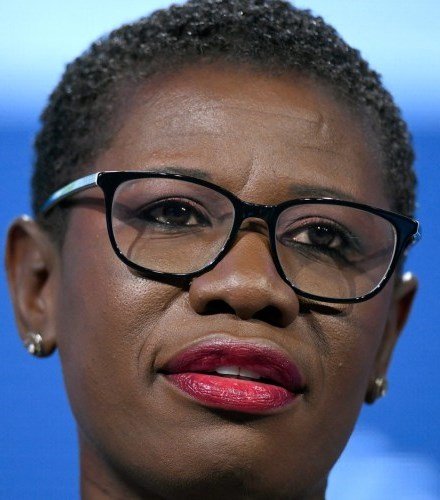

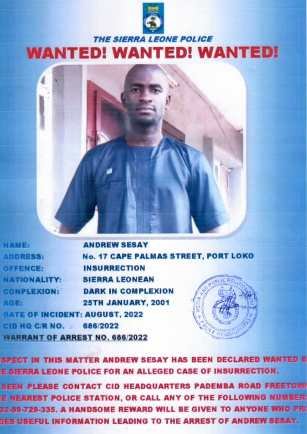

Context: Removal Proceedings of the Auditor General

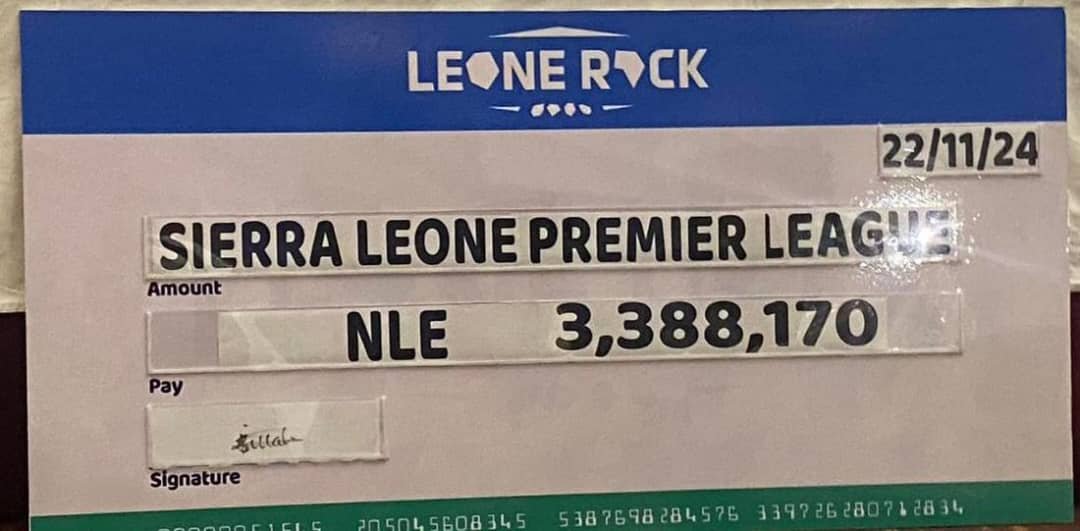

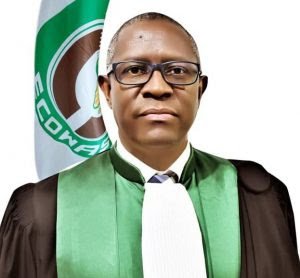

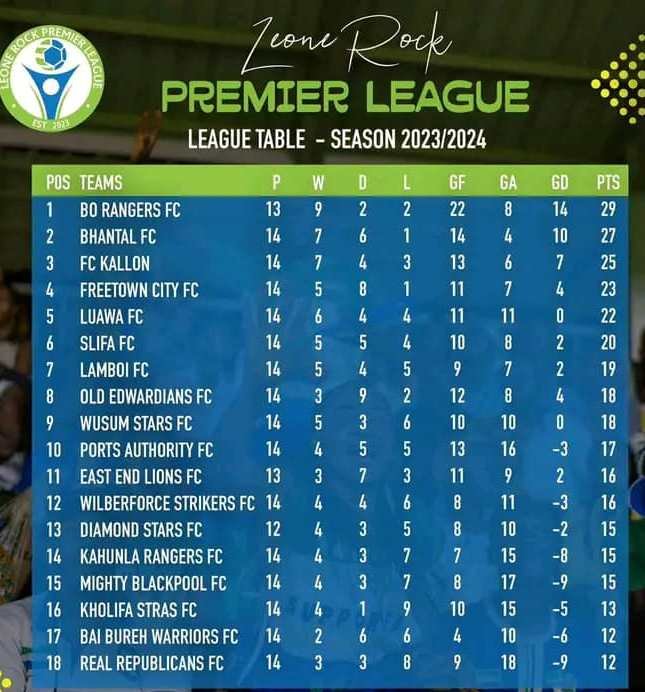

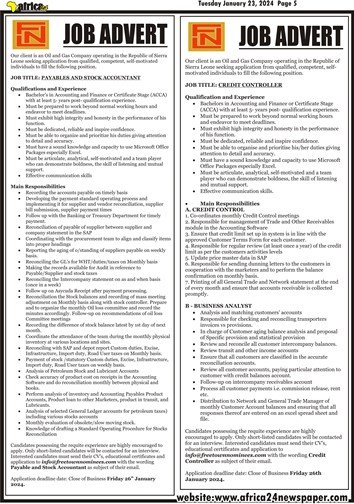

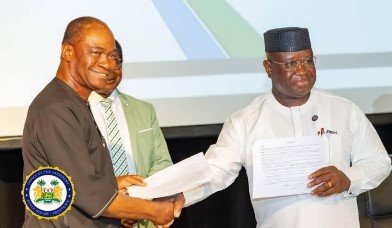

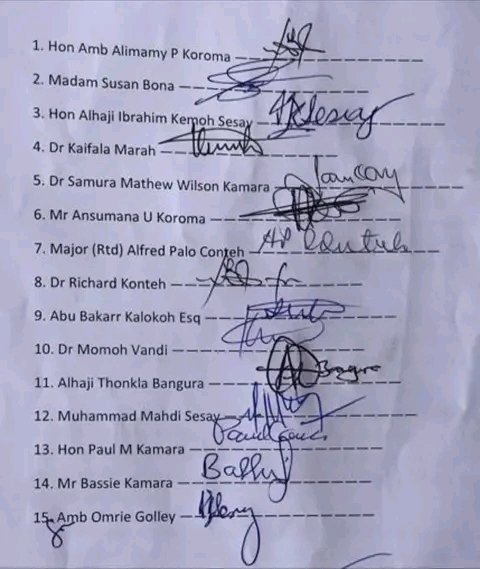

The constitutional basis for Lara Taylor-Pearce’s removal stemmed from Sections 119(9) and 137(7)(b) of the Constitution of Sierra Leone (1991), which require parliamentary approval by a two-thirds majority “in Parliament.” The Speaker ruled that “in Parliament” referred to members present and voting, rather than the total number of elected Members of Parliament. This interpretation enabled Parliament to resolve the matter efficiently, with 100 votes in favor of removal, 36 against, and 1 void (constituting 67% of members present and voting). The ruling demonstrated Parliament’s capacity to act on the tribunal recommendations while operating within procedural confines.

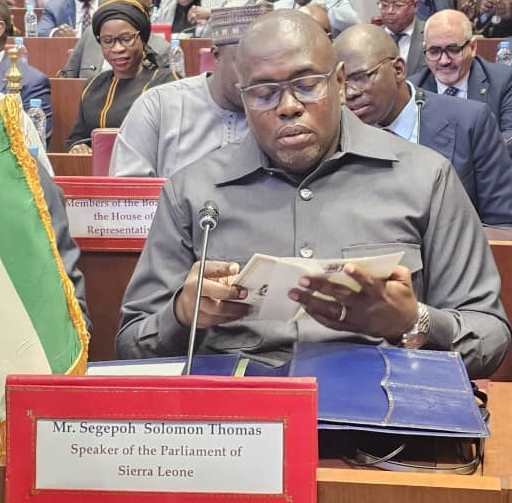

The Speaker’s Ruling: A Constitutional Interpretation

The Speaker’s interpretation centered on the preposition “in” as a spatial qualifier, distinguishing between members physically present in the parliamentary chamber (“in Parliament”) and the broader assembly of elected representatives (“of Parliament”). This reasoning aligns with Erskine May’s principle that “parliamentary language must be construed in its ordinary sense unless context dictates otherwise” (Erskine May, 2023, p. 45). While some legal scholars and critical voices questioned whether the framers of the Constitution intended “in Parliament” to signify members present and voting, the Speaker’s ruling adhered to the constitutional text as written, prioritizing procedural certainty over speculative intent (Jalloh, 2024).

This ruling was not without controversy, as critics argued that a stricter interpretation, requiring the participation of two-thirds of all elected Members of Parliament, might have better reflected democratic principles. However, the Speaker’s approach aligns with parliamentary precedent, where quorum-based voting has frequently been upheld as a valid legislative mechanism (Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, 2021).

Comparative Perspectives from Commonwealth Parliaments

Sierra Leone’s approach reflects the diversity of parliamentary mechanisms across Commonwealth jurisdictions in addressing the removal of Auditor General. A comparative analysis highlights key distinctions:

- Ghana: Requires judicial tribunal findings and parliamentary approval by a two-thirds majority of all members (Constitution of Ghana, 1992, art. 146).

- Canada: The Auditor General is removable via parliamentary resolution for cause, with strong public accountability mechanisms ensuring transparency (Auditor General Act, 1985, s. 3.1).

- Australia: Bipartisan parliamentary approval is required before the Governor-General may remove the Auditor General (Auditor-General Act, 1997, s. 30).

- Kenya: The 2010 Constitution introduced explicit safeguards for removing independent officers including the Auditor General. Article 251(1) requires a petition to Parliament, an inquiry by a tribunal, and approval by a two-thirds majority of all Members of Parliament (Constitution of Kenya, 2010). This clear phrasing eliminates interpretive ambiguity, ensuring that decisions reflect the will of the full legislature.

- Uganda: Contrasting with Kenya’s strict procedural requirements, Uganda’s approach has been more flexible. In 2017, the removal of Auditor General John Muwanga faced challenges due to procedural irregularities (Kasozi, 2020). The Ugandan Parliament approved the removal with a simple majority of members present and voting, despite opposition arguing for a higher threshold. Subsequent court rulings declined to intervene, reinforcing Parliament’s interpretative discretion. Uganda’s case underscores the risks associated with procedural ambiguity, particularly in contexts where executive influence over Parliament is significant (Mwenda, 2021).

Sierra Leone’s hybrid model—incorporating tribunal findings, executive communication, and legislative action—demonstrates a unique adaptation of Commonwealth principles. While some scholars argue that Kenya’s explicit constitutional phrasing (“all members of Parliament”) offers greater clarity (Constitution of Kenya, 2010, art. 251), Sierra Leone’s process underscores Parliament’s role as the final arbiter in constitutional questions having to do with its systems and processes (Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, 2021).

Implications for Parliamentary Practitioners

- Procedural Precision: The case highlights the need for unambiguous constitutional language. Ghana’s requirement for a two-thirds majority “of all members” eliminates ambiguity (Constitution of Ghana, 1992). Sierra Leone’s experience may encourage drafters to adopt similar specificity in future reforms.

- Role of the Speaker: The ruling reaffirmed the Speaker’s authority to interpret procedural rules, a cornerstone of parliamentary sovereignty (Erskine May, 2023). This aligns with the Ugandan Speaker’s role in guiding complex constitutional debates (Kasozi, 2020), illustrating a shared Commonwealth tradition.

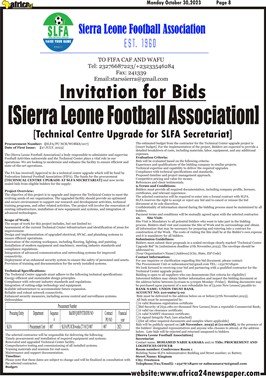

- Interbranch Collaboration: The use of Standing Order 14(1) (b) to facilitate executive-legislative communication reflects pragmatic governance within the rules, though it invites scholarly debate about the optimal separation of powers (Institute for Governance Reform, 2024).

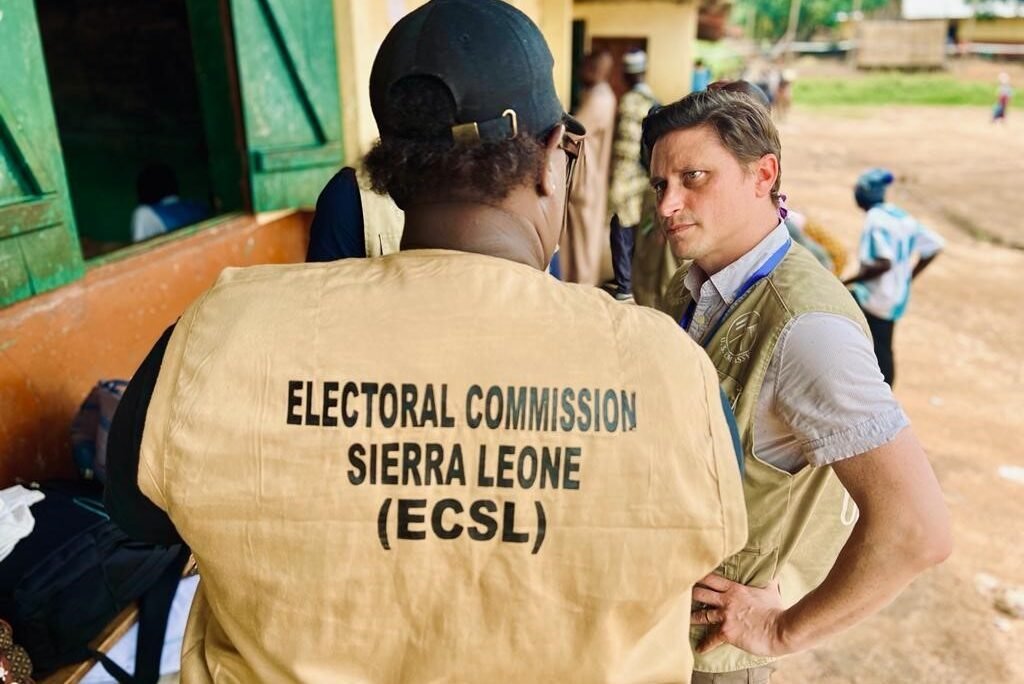

Public and Institutional Response

The removal process prompted significant civic discourse, with organizations like Sierra Leone’s Integrity Advocacy Consortium (IAC) advocating for clearer constitutional safeguards (IAC, 2024). International observers, including the Commonwealth Secretariat, viewed the removal as a learning opportunity for refining procedural frameworks (Commonwealth Secretariat, 2024).

Conclusion

The Speaker’s ruling on the prepositional phrases “in Parliament” and “of Parliament” illustrates the interplay between constitutional text, procedural rules, and institutional roles. Sierra Leone’s experience contributes to Commonwealth parliamentary scholarship by demonstrating how linguistic interpretation can resolve constitutional ambiguities. Future reforms could enhance clarity by adopting phrasing such as “two-thirds of all members,” as seen in Kenya and Ghana, while preserving Parliament’s interpretative authority. As Erskine May observes, “The strength of parliamentary democracy lies in its adaptability to constitutional challenges” (Erskine May, 2023, p. 204). Conclusively, this removal proceeding provides essential lessons for parliamentary practitioners navigating constitutional and procedural complexities.

References

Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (2021) Model Law for the Appointment and Removal of Independent Officers. London: CPA Secretariat.

Commonwealth Secretariat (2024) Parliamentary Governance and Procedural Integrity. London: Commonwealth Publications.

Commonwealth Secretariat (2024) Statement on Sierra Leone’s Parliamentary Proceedings. London: Commonwealth Secretariat.

Constitution of Ghana (1992) Government of Ghana. Accra: Government Printing Press.

Constitution of Kenya (2010) Government of Kenya. Nairobi: Government Printer.

Constitution of Sierra Leone (1991) Government of Sierra Leone. Freetown: Government Printing Press.

Crystal, D. (2008) A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th edn. Oxford: Blackwell.

Erskine May, T. (2023) Treatise on the Law, Privileges, Proceedings and Usage of Parliament. 26th edn. London: Butterworths.

House of Parliament of Sierra Leone (2023) Standing Orders of the Parliament of Sierra Leone. Freetown: Parliamentary Publications.

Integrity Advocacy Consortium (2024) Press Release: Strengthening Constitutional Safeguards. Freetown: IAC.

Institute for Governance Reform (2024) Parliamentary Practice in Sierra Leone: A Technical Review. Freetown: IGR Policy Brief.

Jalloh, M. (2024) ‘Constitutional Interpretation in Sierra Leone: A Case Study’, African Journal of Comparative Law, 12(3), pp. 45–67.

Kasozi, A. (2020) Executive Influence and Parliamentary Oversight in Uganda. Kampala: Makerere University Press.

Kasozi, J. (2020) Parliamentary Governance in Uganda: Traditions and Innovations. Kampala: Fountain Publishers.

Mwenda, A. (2021) Judicial Restraint and Political Processes in Uganda. Nairobi: East African Publishers.

Ochieng, J. (2017) Kenya National Commission on Human Rights v. Attorney General. Kenya Law Reports.

Disclaimer

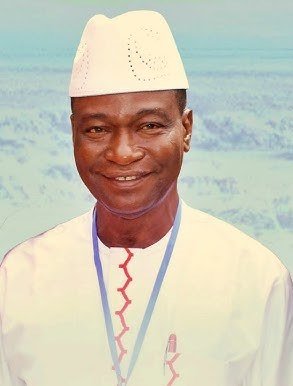

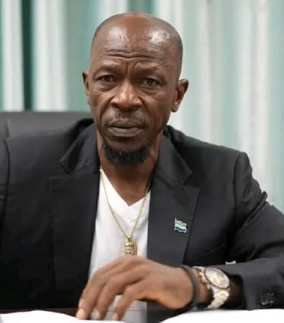

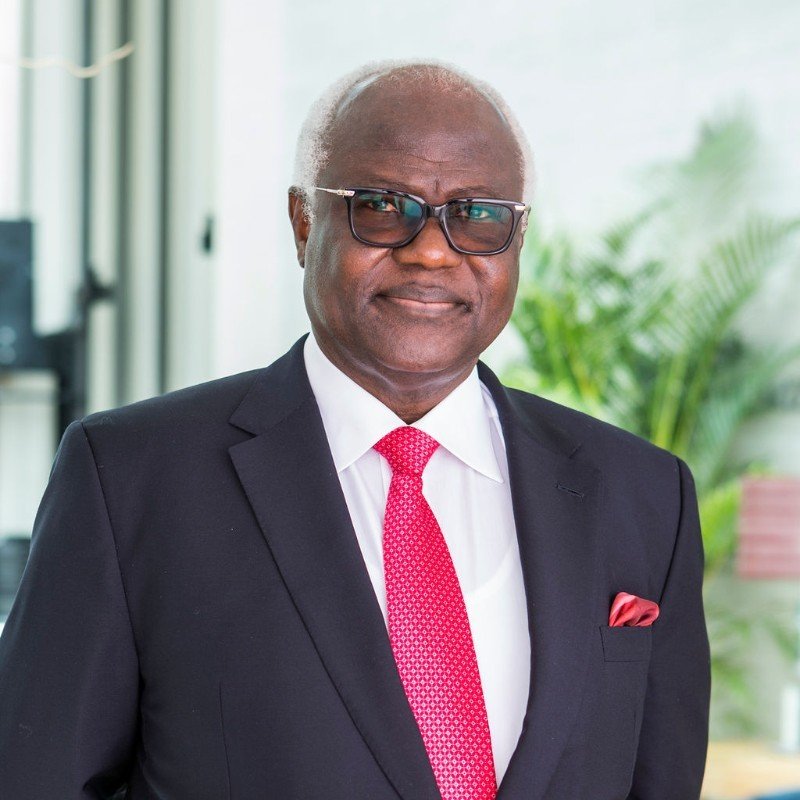

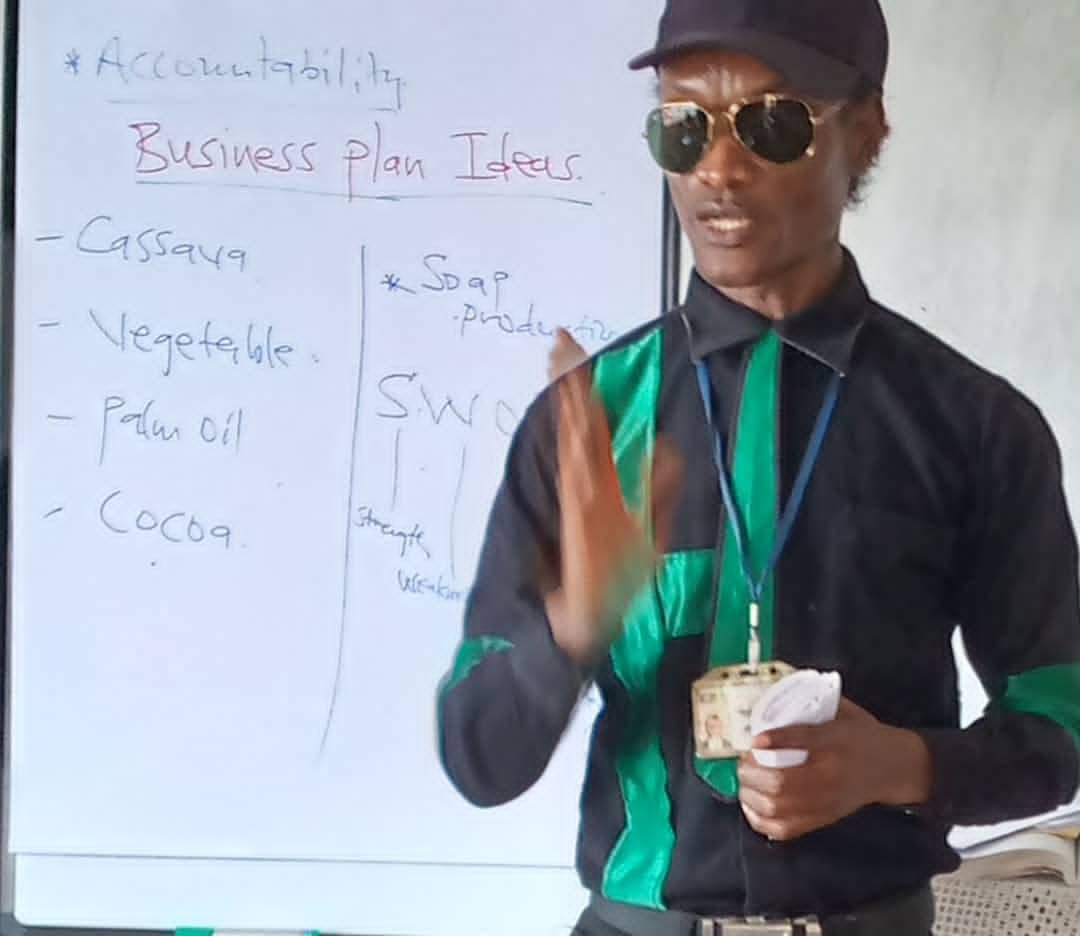

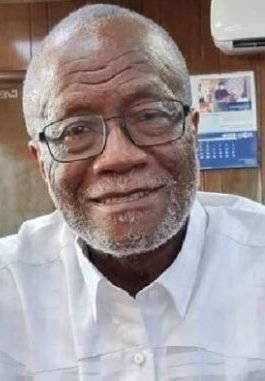

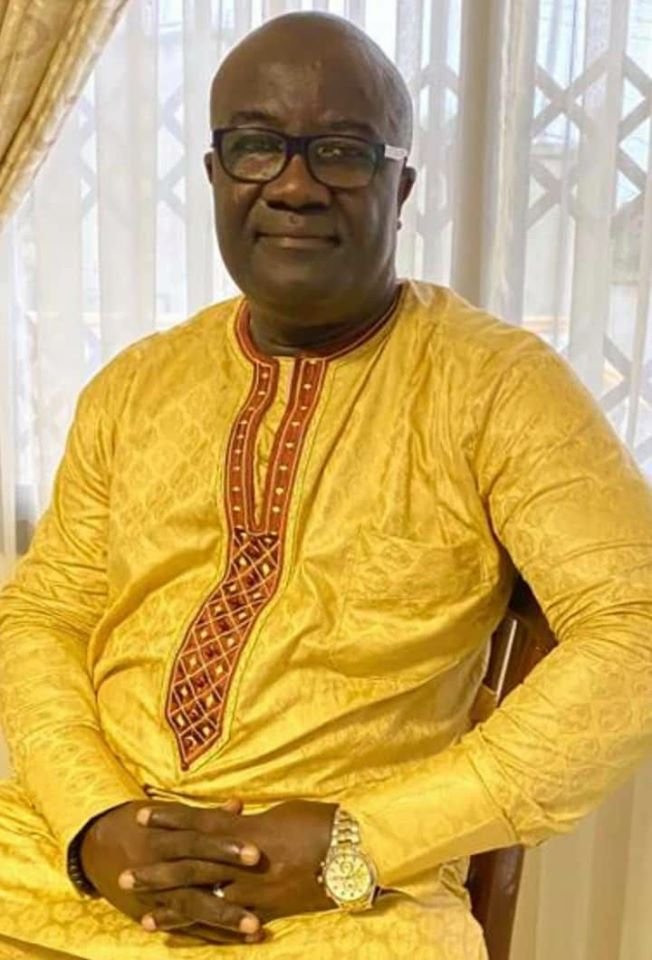

Momodu – Lamin Deen Rogers is currently the Director of the Legislative Services Parliament of Sierra Leone and a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone.

The views, analyses, and conclusions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official position or endorsement of the Parliament of Sierra Leone or any entity with which the author is affiliated.

He acknowledges the potential intersections between professional and academic roles but emphasizes that this work constitutes independent scholarly research.

Invariably, the article does not seek to advance institutional agendas, nor has the author’s institutional role influenced the scholarly framing, evidence, or arguments presented. Academic freedom and intellectual integrity remain central to this work, despite the sensitivities of the political ecosystem in which the article is birthed.

The political environment discussed is inherently complex and subject to diverse interpretations – while the author endeavored to maintain rigorous academic standards—including objectivity, methodological transparency, and critical engagement with sources—this article reflects the author’s analysis in hindsight. Any errors or omissions are the author’s own. Citations of individuals, groups, or events are intended solely for academic discourse and should not be interpreted as endorsement, criticism, or advocacy beyond scholarly inquiry.