By Hassan I. Conteh

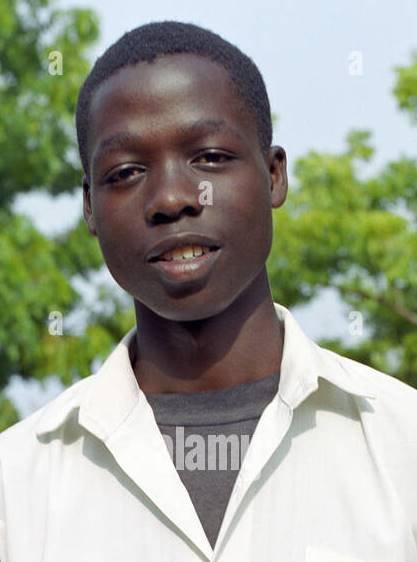

Early February, Salamatu Kainesse, a lactating mother, fears that a well in their community may dry up in the middle of the dry season.

She now worries over the discomfort it would cause on her anytime soon.

“The water, referring to a ground water, sometimes gets dirty. So, you need to wake up five in the morning to get clean water,” she explains.

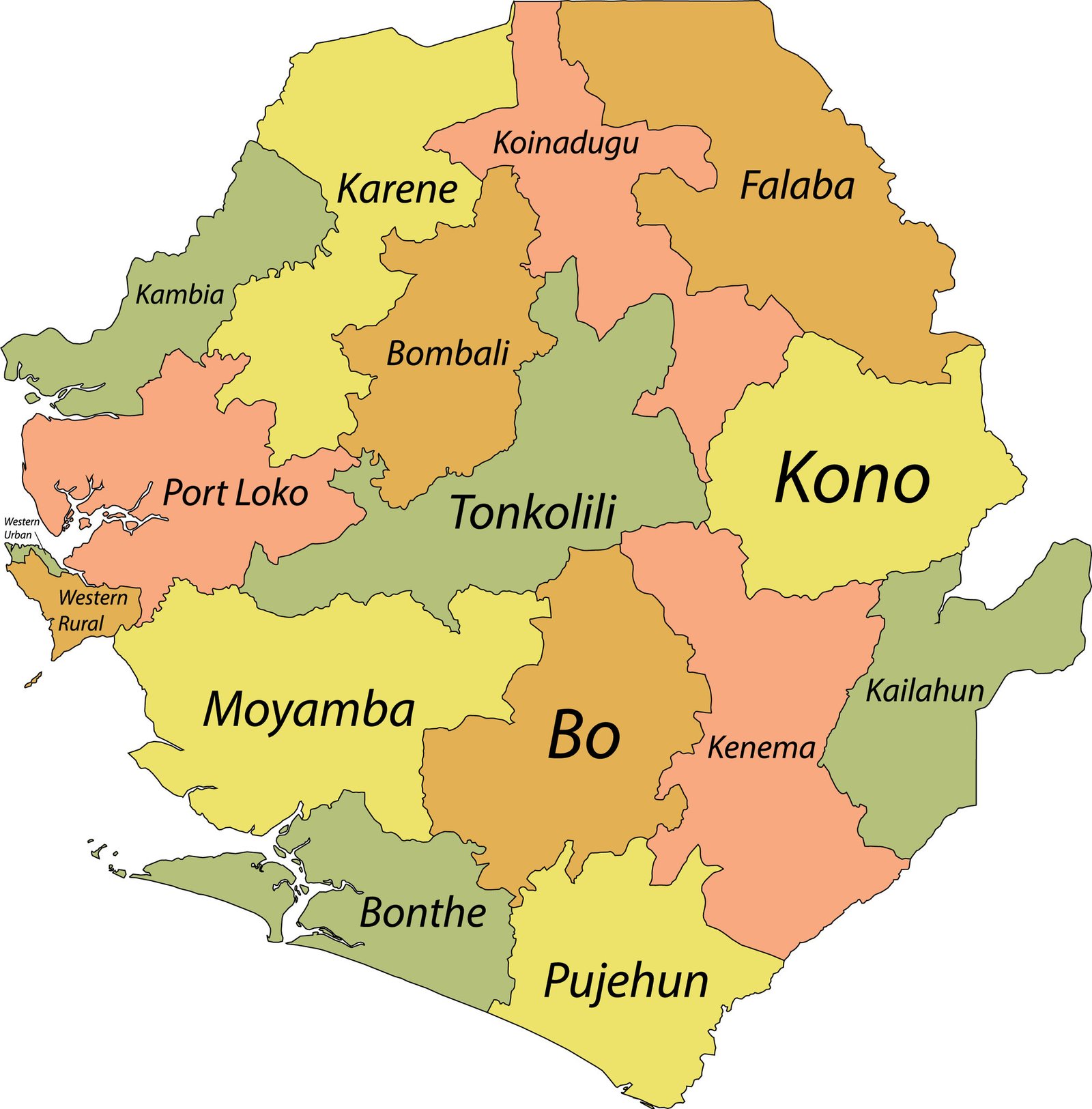

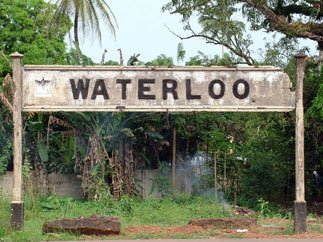

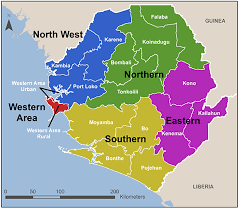

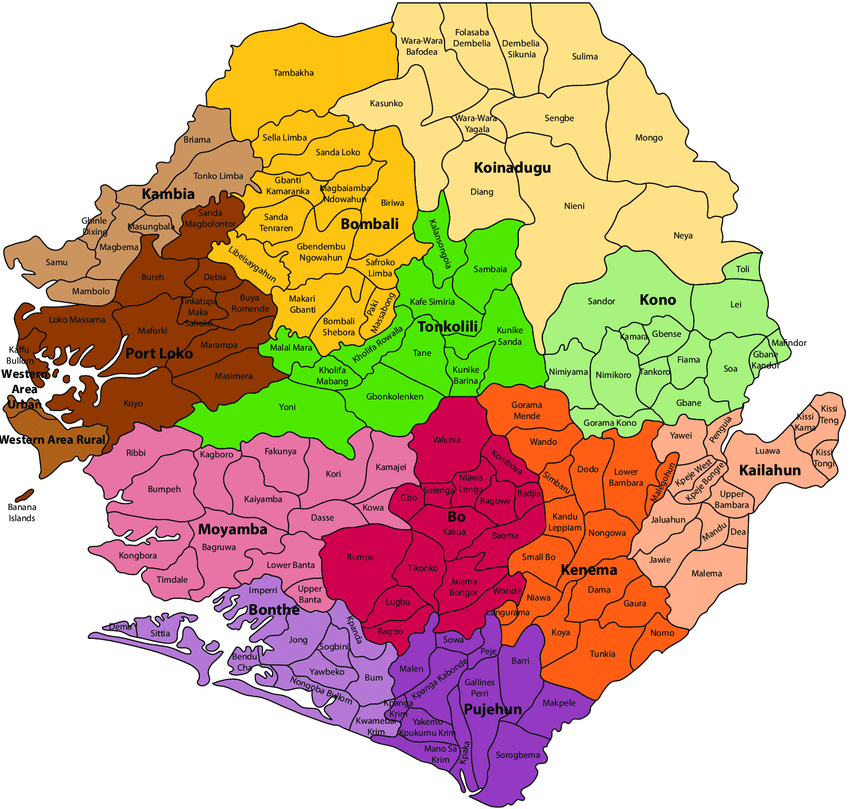

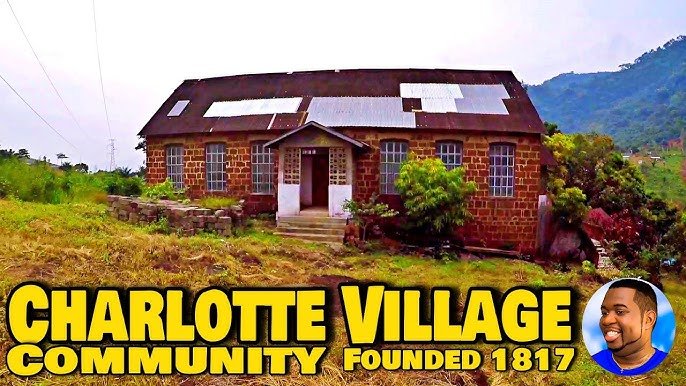

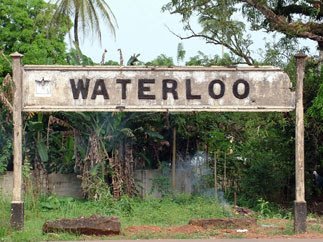

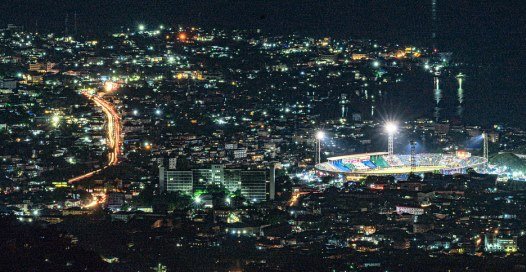

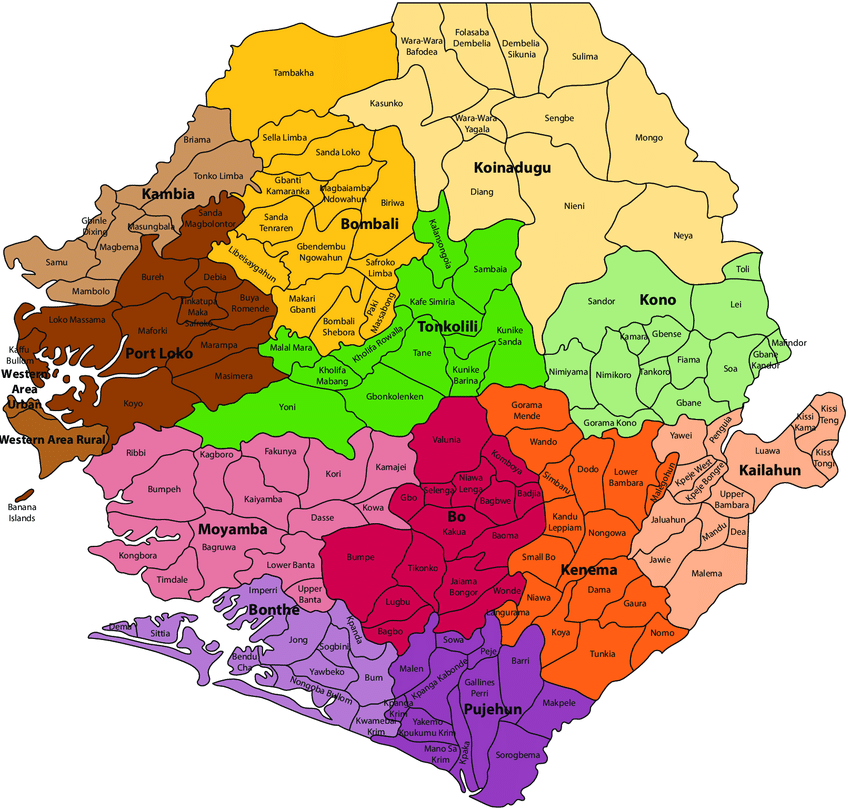

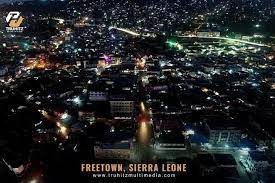

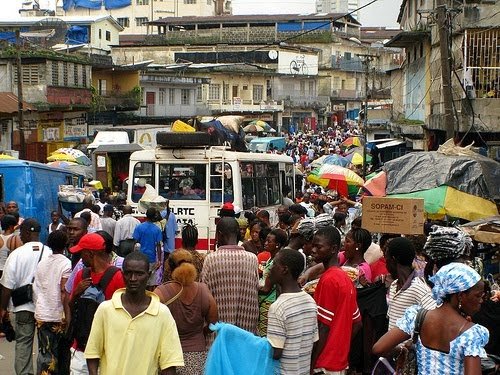

Her situation is similar to others who live in Sierra Leone’s capital Freetown, built at the foot of mountains on the Atlantic Ocean on Western African coast.

During the dry season, residents on hilltops, and those on the outskirts usually get water from dug- out wells.

But some wells have completely been dried up over the years.

The wells dry as people rapidly cut down the trees to build homes or grow vegetables.

As a result of this bad practice, the soil which holds up the water becomes exposed hence water crisis and mudslides occur.

Freetown has suffered devastating floods and a mudslide in August 14, 2017 alone killed more than 1,000 people, according to government officials’ report.

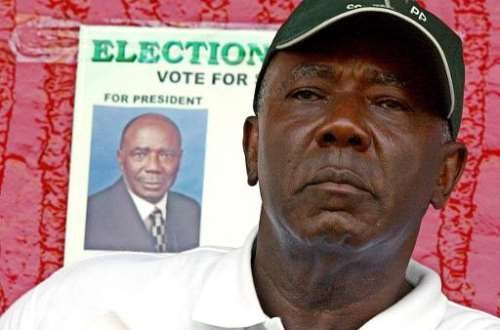

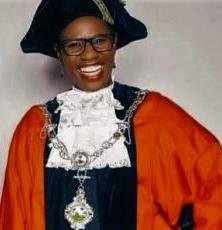

“I think the biggest challenge is a lack of appreciation of how quickly the deforestation is happening and how far-reaching the impact is,” mayor Aki-Sawyer, told Reuters Foundation, few years ago in an interview.

As water crisis hits most communities in the capital city, Kainesse including others will move to Botany, a swampy area where wells owned by private community individuals are sprawling about. It is located at Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone, which is just half a mile away from her residence at Mount Aureole community.

At dries especially between March and April, it is common to see school-goers fetching water from some narrow holes being created by rocks blasted by road construction workers.

On the grid of the city, the situation is appalling as women and girls grope for water-cut- pipes found on street gutters, to fill up their gallons (jerry cans).

The wet season, however; often brings smiles to the likes of Mrs. Kainesse who would trap the rain using buckets placed under their house ceilings.

However, promises made by successive governments to fix the city’s water crisis have all turned to windy hopes for residents who now pay heavy price due to state’s failures.

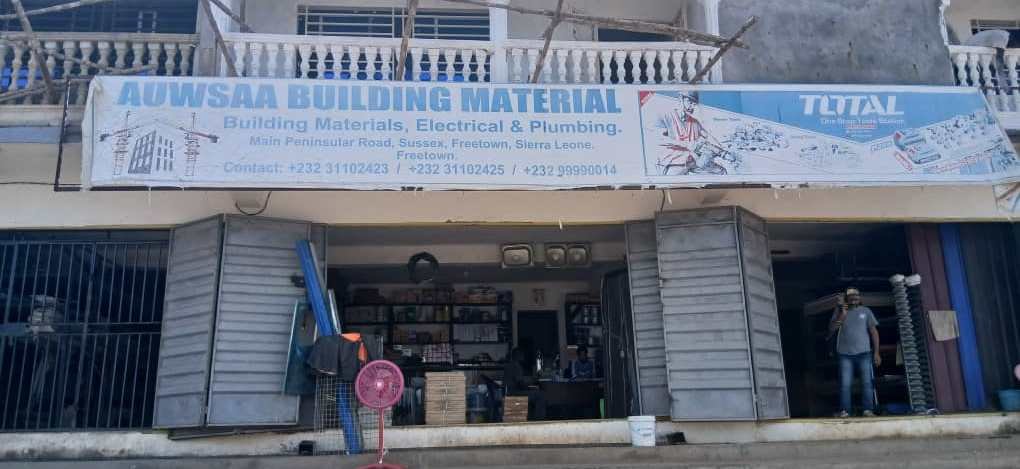

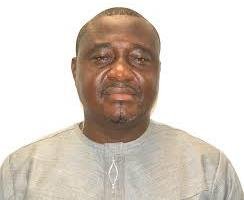

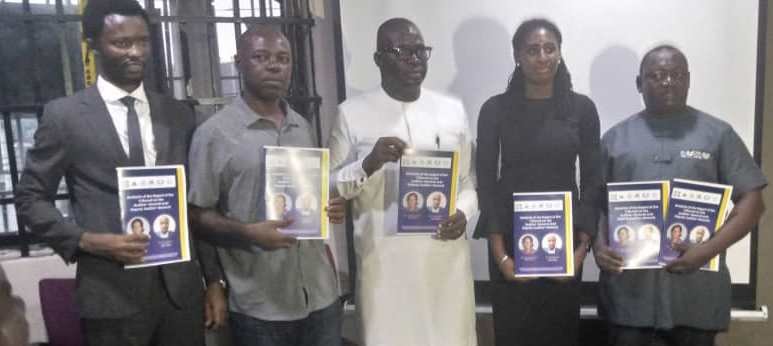

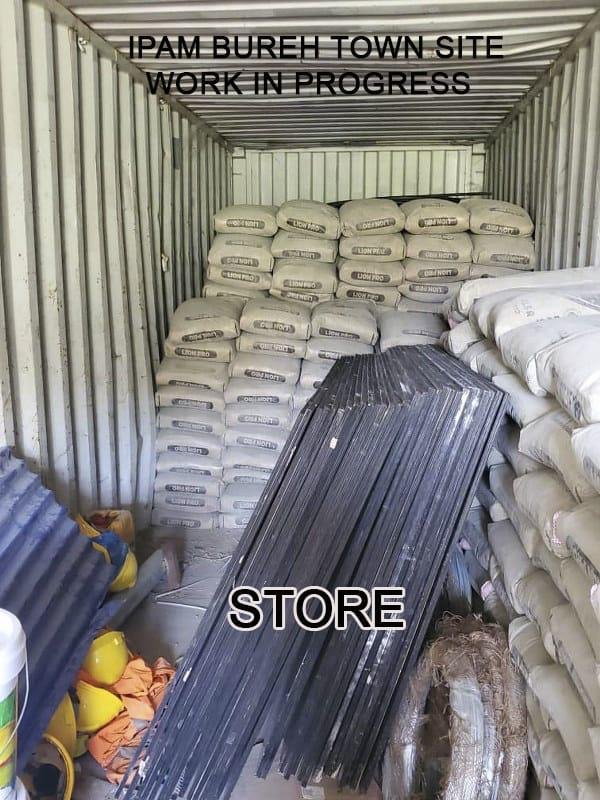

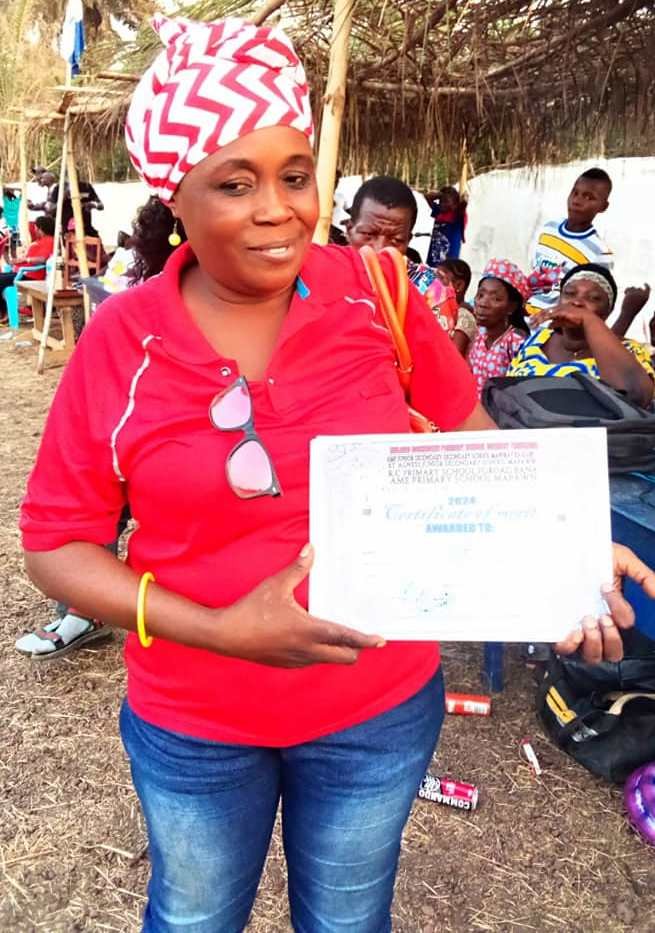

“We spend at least Le 100 million ($ 10,000) that was around 2019, to build and rehabilitate fifteen taps,” says Haroun Conteh, a spokesman for a community organization, Kossoh Town Descendants in the east of the capital.

Conteh said it took them months before getting approval from a state supplier of water, Guma Valley Water Company (GVWC) as it was paid to get the equipment installed in the community.

Other deprived communities are taking similar ventures by building taps through their little contributions they make.

Already, Together for Development Organization ( TDO), a social services club, at Mountain Cut, central of Freetown, has built a raised platform for a ‘milla tank’ or bowser, but a bowser is yet to be provided by their MP, Alhaji Alhadi Lihadi, as promised earlier.

“The community people have lost trust in us owing to several delays to get the taps functional,” Alie Bangura, TDO’s member, complains.

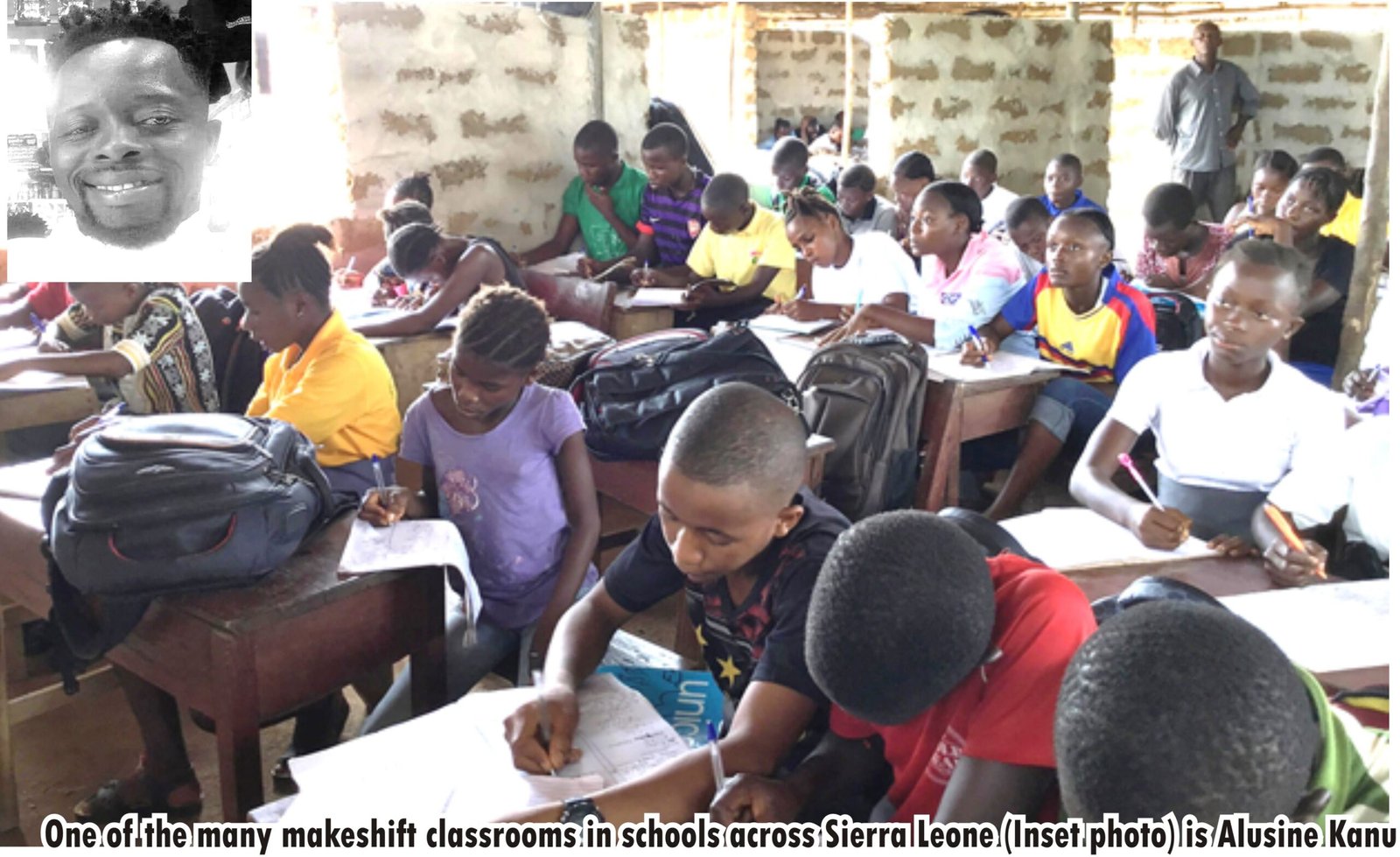

Bangura says pupils are affected by this with their night studies as they have to trek hills dotted with cobbles in search of clean water.

About 40.6 per cent of at least 14, 854 households in Freetown suffer from un-improved drinking water, sanitation and hygienic service, according to Sierra Leone Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey of 2017.

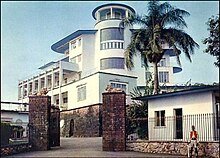

The Guma dam, the only one where the city gets its clean water, couldn’t supply a population nearing 2 million people.

Back as a British colony, Freetown’s Guma Water Treatment Plant, built in the 1960s, was sized to only supply water to at least 800,000 residents.

Experts say other dams are needed and Western Peninsula forest reserves must be protected. And currently, dry spells are affecting Freetown’s biggest water reservoir, the Guma dam. This is due to local climate changes and the forest fires by people around.

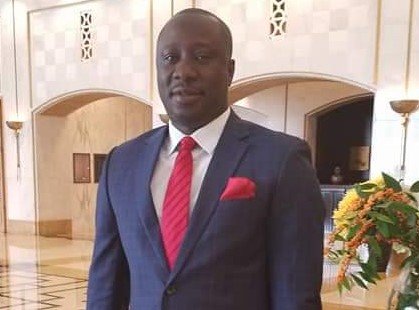

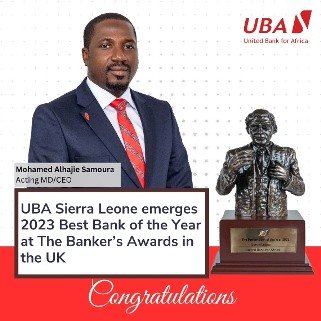

Also, the dam is not only small to serve the capital’s population but its water is not well-managed by the government. GVWC’s director, Maada S. Kpenge, posted on Twitter ( now X) that because of early spillage in the Guma, Freetown might experience water shortage the following year.

GVWC, in October 2023, warned of water shortage as it said when the dam is full it leads to “excess of water” running into the Number Two River into the Atlantic Ocean.

The government has adopted a policy to plant more trees to save the Guma dam.

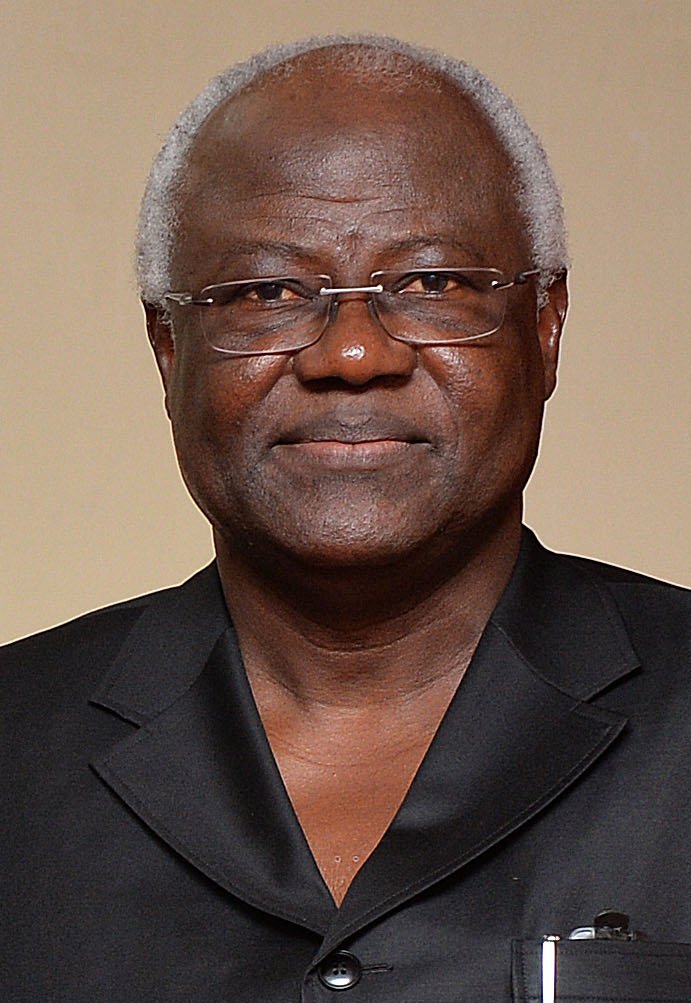

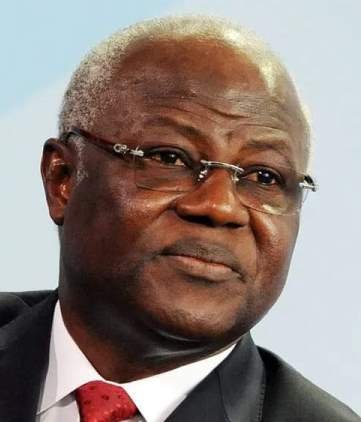

To recover the lost trees, President Julius Maada Bio, unveiled a National Tree Planting project (NTPP) which has seen about 1.2 million trees being planted in 2021 alone.

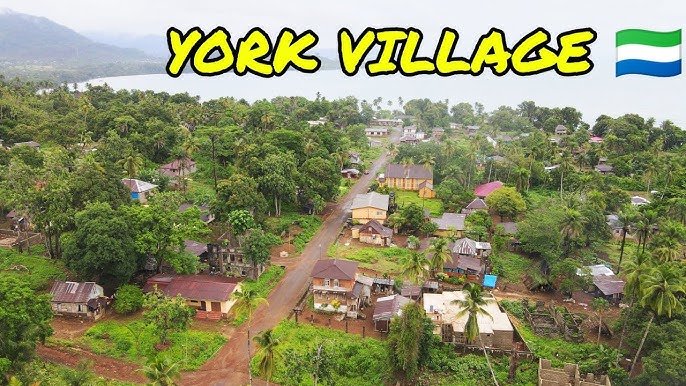

Complementing government’s tree planting project, DHL, a mail and logistics firm, has also planted about 500 trees at York village in Western Area Rural District.

“We aim to plant at least 5 million “economic trees” across the country in next three years. We’ve also launched a campaign telling people that when you cut one tree; plant three more,” says, Lahai Kpaka, Information officer at Ministry of the Environment.

Government’s campaign to plant more trees dovetails with a global campaign for a ‘green world’ that is safe for humans, giving more focus on climate change issues.

But, in the midst of tree planting, provincial forests now face huge challenges as government lifts a ban on timber logging in the country.

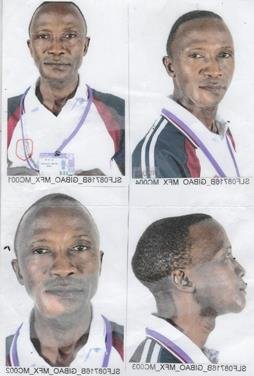

Sierra Leone government is the sole exporter of timber despite widespread criticisms that it is monopolizing the trade and authorities are not transparent.

For instance, Sierra Leone’s 2019 Audit Service revealed that timbers are shipped to overseas as they are loaded in full cargo containers other than using the standard cubic measurement which is widely recommended. The illegal measurement of the logs results to huge loss in government’s revenues.

And as tree-trunks are shipped overseas, the environment ministry is aware of the risks it causes to the forests and the soil.

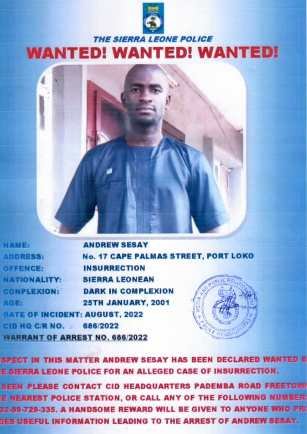

Kpaka admits that Freetown’s catchments are under “serious threat” and encroachers would have to face police arrests.

“The ‘green belt ‘or hilltops demarcation points have been encroached especially in the Western peninsula rural environments,” he noted.

An inter-ministerial committee, he assured, had been set up with the aim to identifying water encroachment areas for an action to be taken.

But the reality on the ground is different from policy makers’ radio and TV sound bites and the poor don’t have access to information about the environment.

President Bio’s environment wing has not fully adopted tougher actions against culprits who ventured into Freetown’s forest reserves to build homes on mountainous communities.

“We’ve conducted series of radio and TV talk shows on the need to protect our environments from being abused,” Kpaka boasted.

Other strategies are needed, however, he added.

To achieve that, Kpaka says, a civil society group is engaging musicians to develop civil messages on the protection of Sierra Leone’s forestry and reservoirs.

But as Sierra Leoneans wait to see if the promises by the environment ministry will yield soon, the worries over the struggle to fetch water in the middle of the dry season will never be over for the likes of Mrs. Kainesse