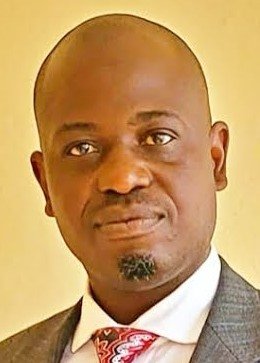

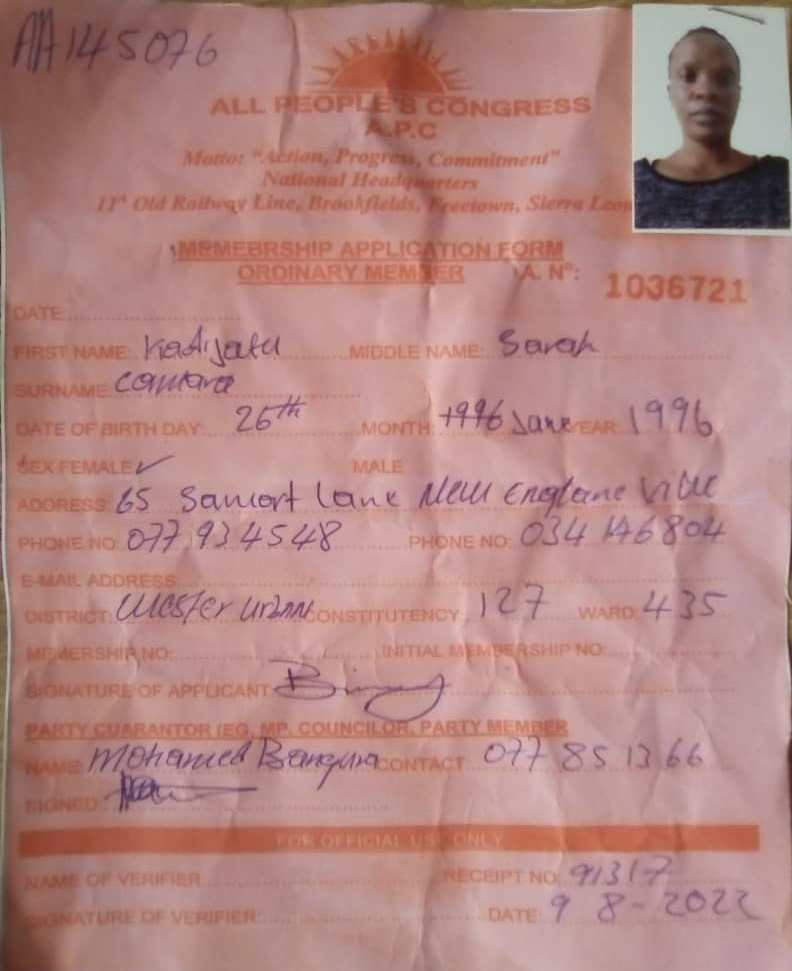

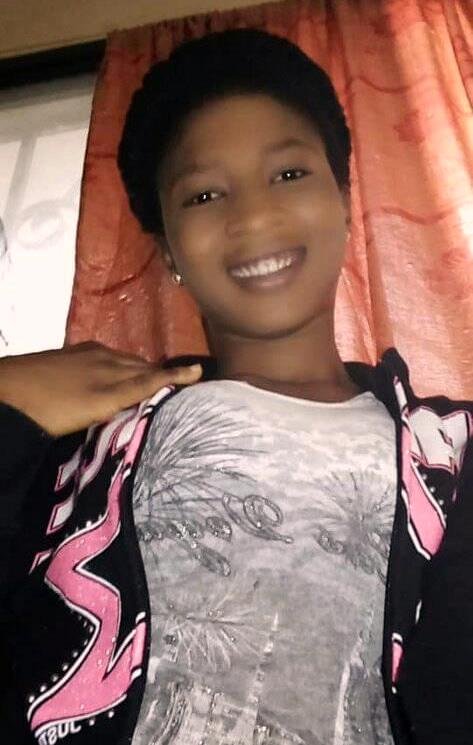

By Mohamed Bangura

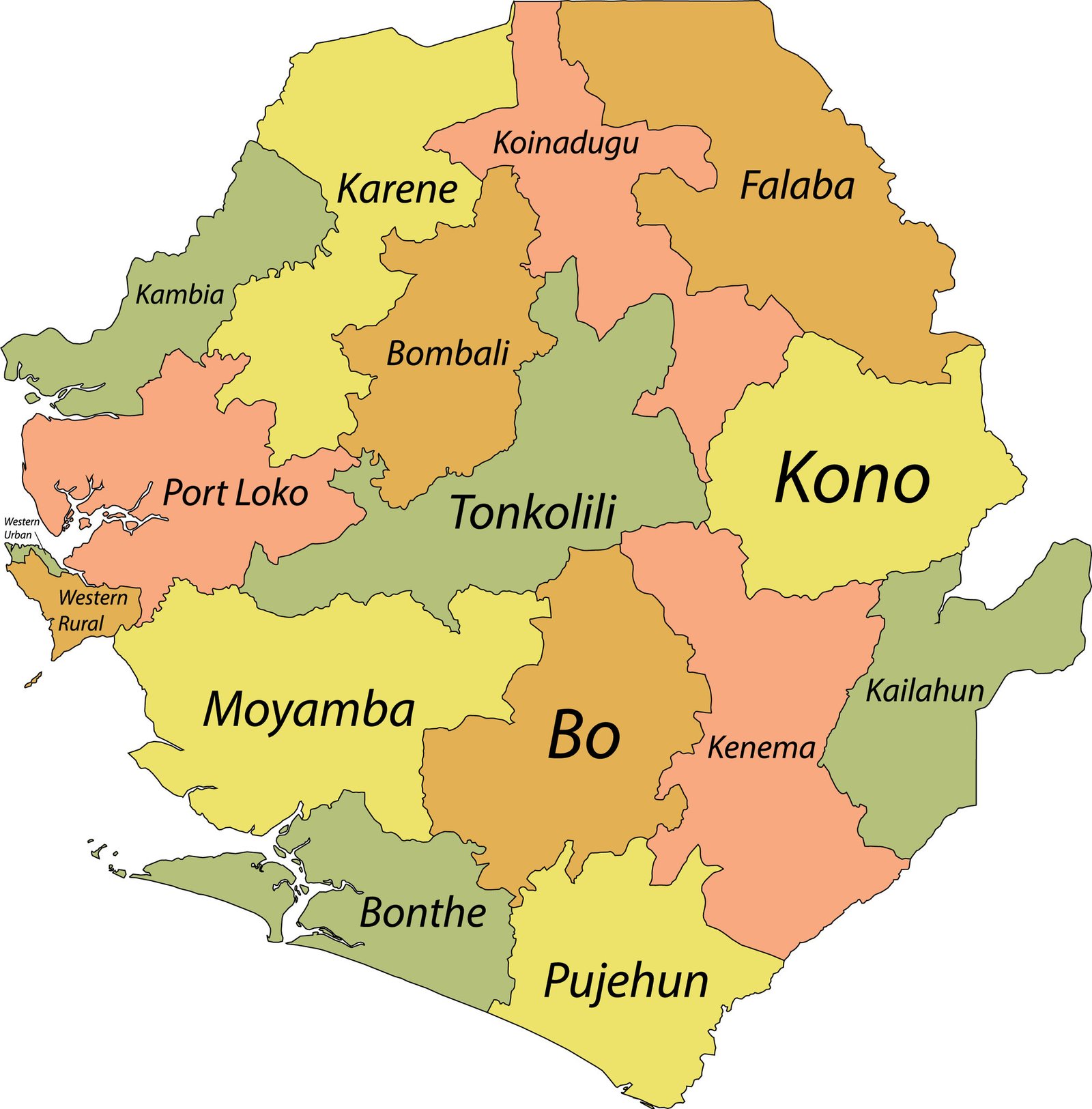

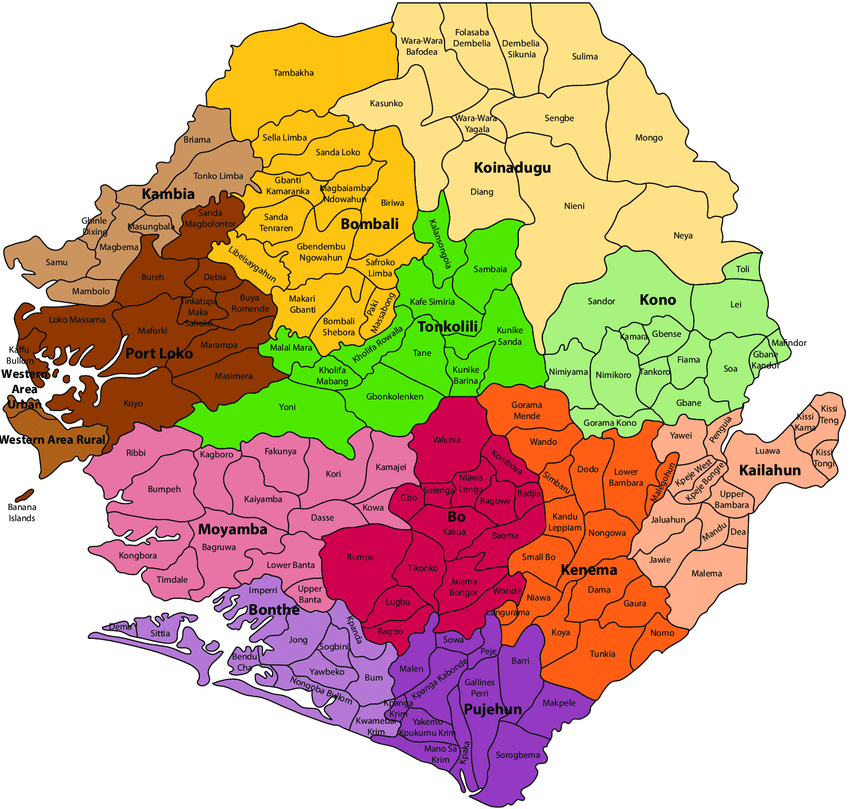

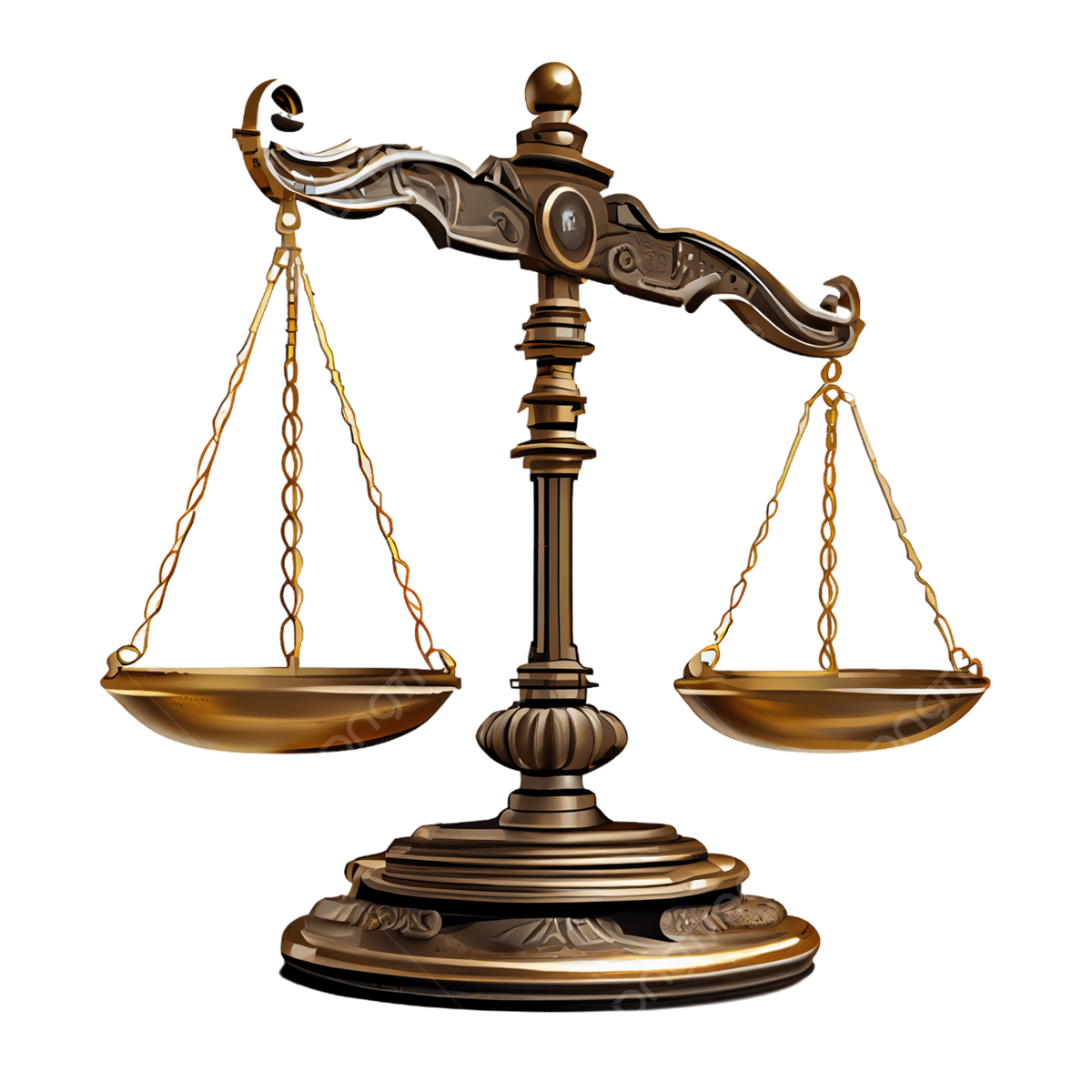

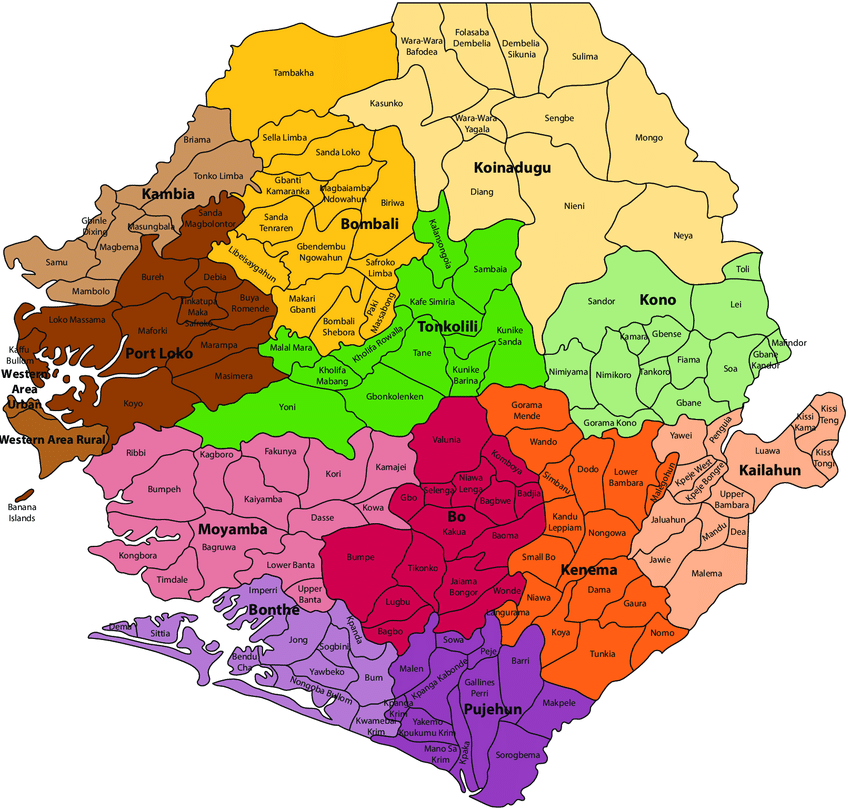

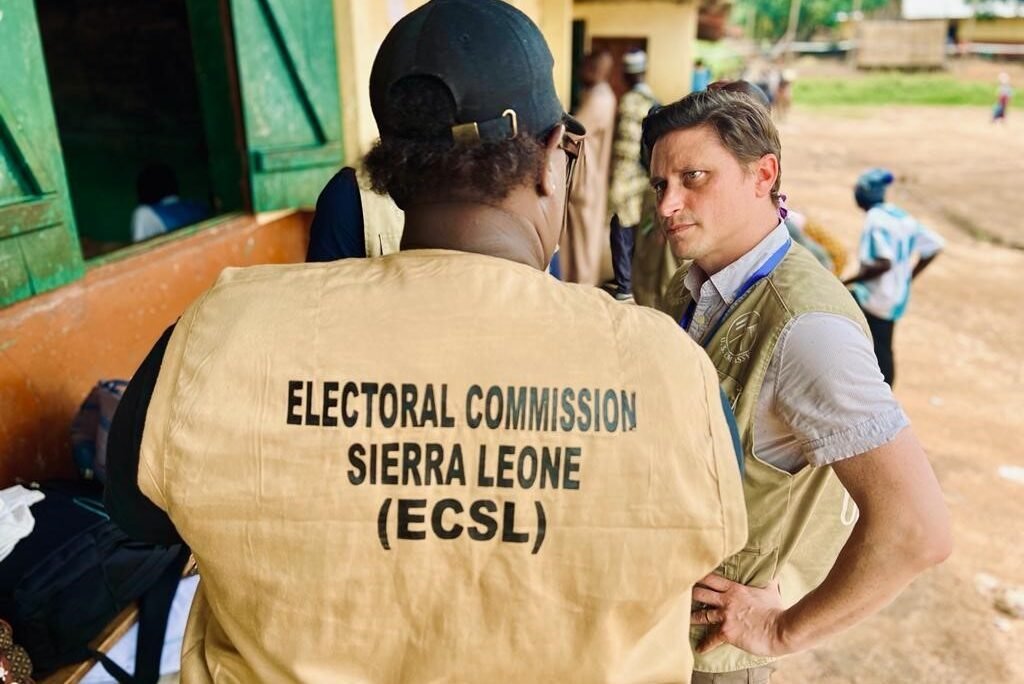

In recent years, Sierra Leone has experimented with different electoral systems, most notably the Proportional Representation (PR) system and the First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) system. While both methods are designed to ensure fair political representation, the PR system has proven to be far more vulnerable to manipulation than FPTP, especially in our country’s fragile democratic context.

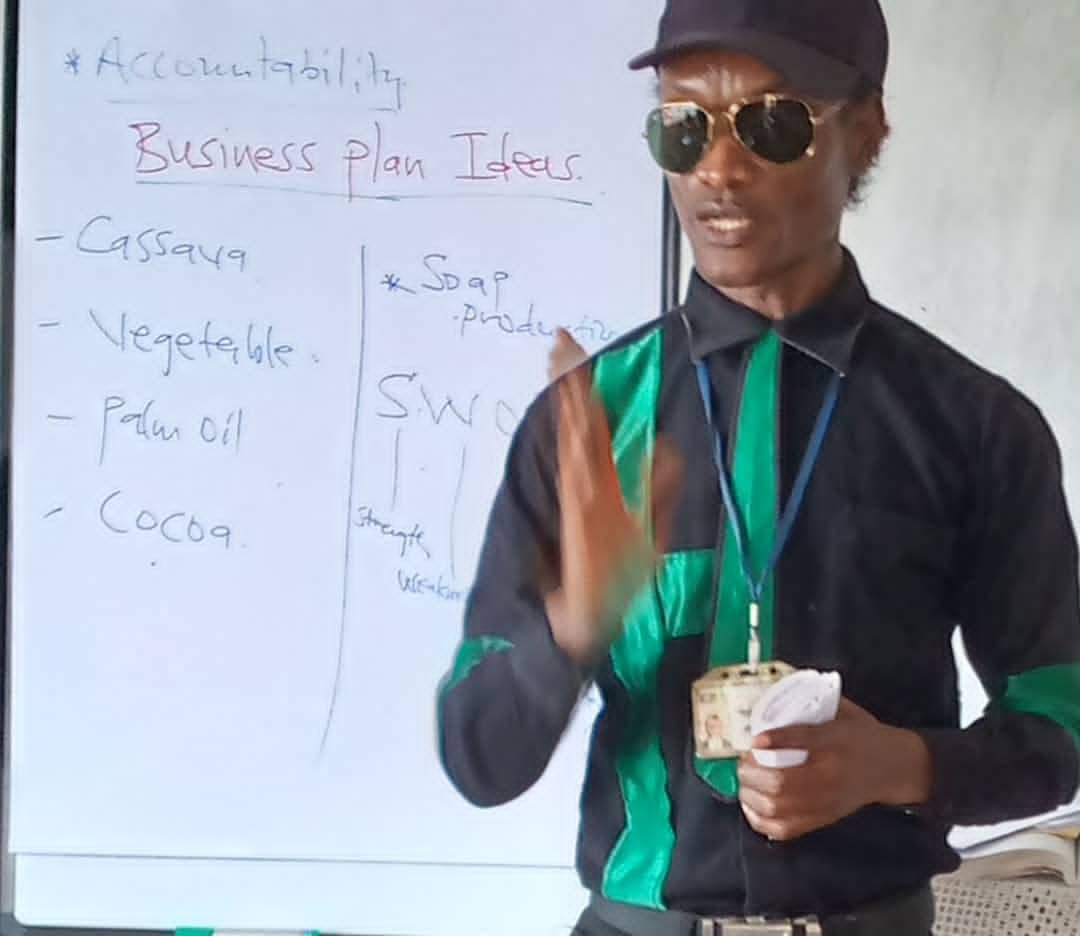

Under the FPTP system, candidates compete in constituencies, and the one with the highest votes becomes the representative. This direct connection between voters and their MPs builds accountability: the people know exactly who to hold responsible if promises are broken. Manipulation at constituency level is much harder because results are localized and easier to verify.

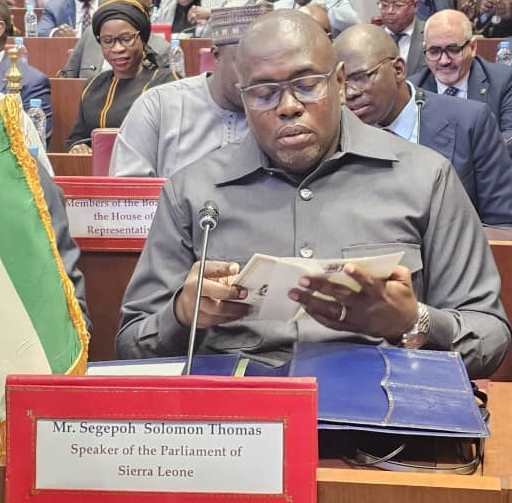

On the other hand, the PR system, which Sierra Leone used in the 2023 general elections, centralizes power in the hands of political parties. Voters do not elect individual candidates but rather vote for parties, which later allocate seats based on a percentage of the total vote. This weakens the link between the people and their representatives. The average voter cannot point to “their MP” because the selection depends on party lists, often controlled by party executives rather than grassroots choice.

More worryingly, the PR system allows for quiet manipulation at the national level. With votes tallied across large districts, it becomes easier to distort figures without immediate scrutiny. Opposition parties and citizens have limited ability to cross-check results at polling stations because outcomes are aggregated over wide areas.

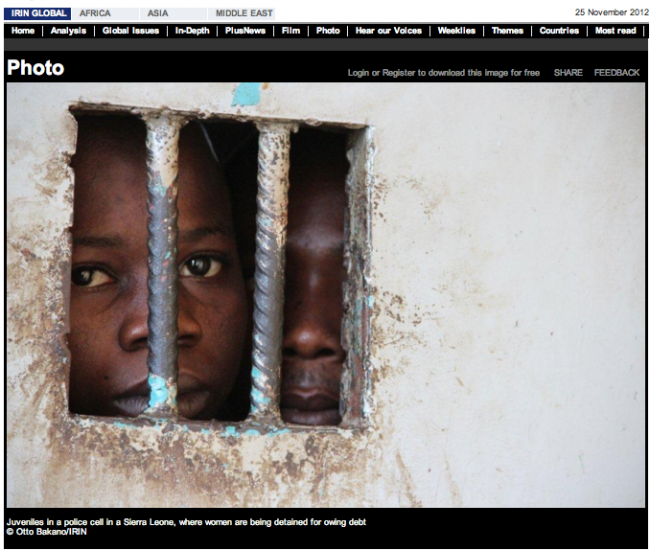

In Sierra Leone, where mistrust in institutions is already high, the PR system risks deepening political tensions. Parties in power may be tempted to exploit their influence over the Electoral Commission to shape outcomes, while smaller parties struggle to gain visibility because the threshold for representation is steep.

It is true that PR was adopted partly to ease political tensions and avoid violent disputes over constituency boundaries. However, in practice, it has concentrated power in the hands of party elites and widened the gap between citizens and their representatives. In contrast, the FPTP system, though not perfect, provides a more transparent process where manipulation is more difficult, and accountability is clearer.

As Sierra Leone continues to reflect on its democratic journey, the debate must go beyond which system is fashionable or convenient. It must focus on which method best serves the people. If democracy is truly about giving citizens a voice, then any system that distances them from their representatives should be questioned.

The lesson is simple: in Sierra Leone’s fragile democracy, the PR system is easier to manipulate, while the FPTP system despite its flaws offers stronger accountability and cleare representation.