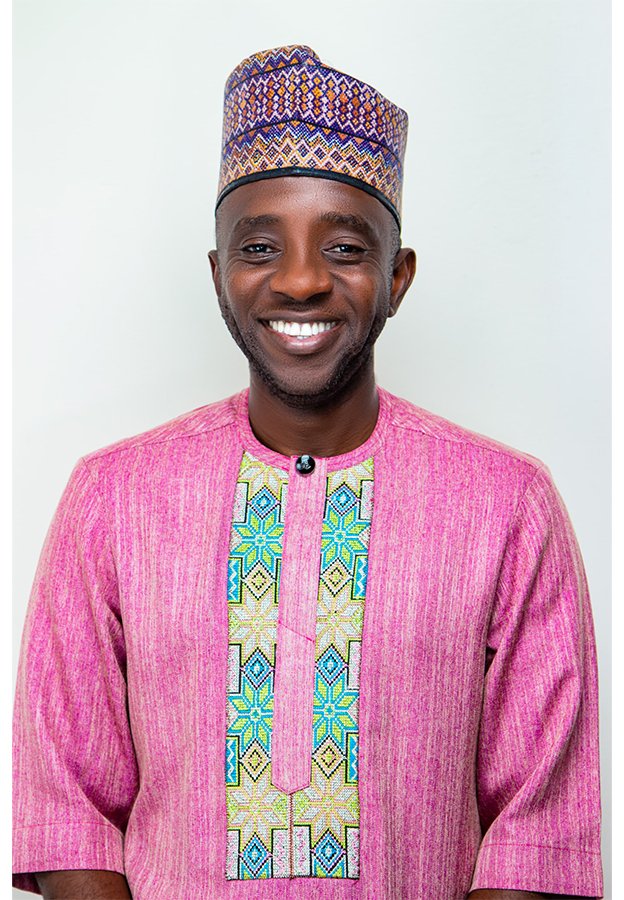

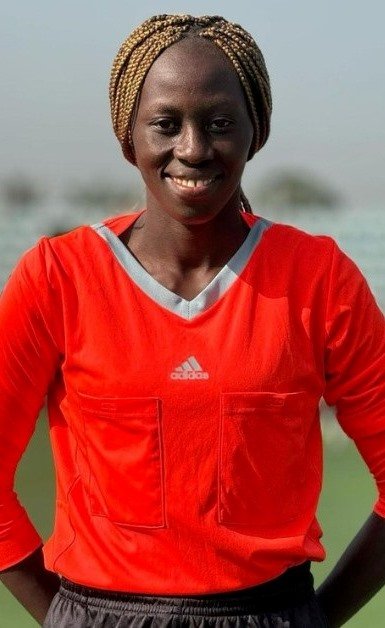

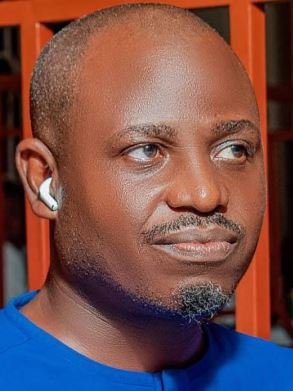

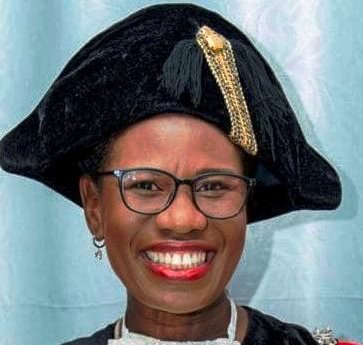

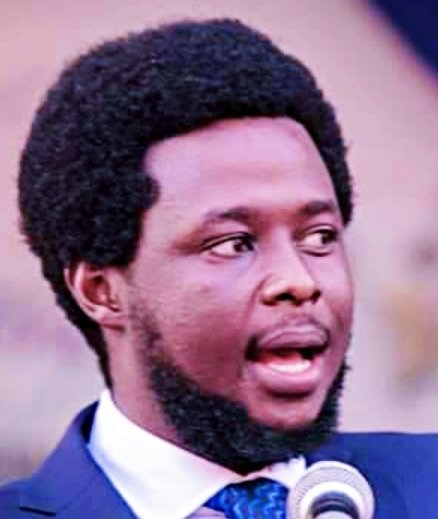

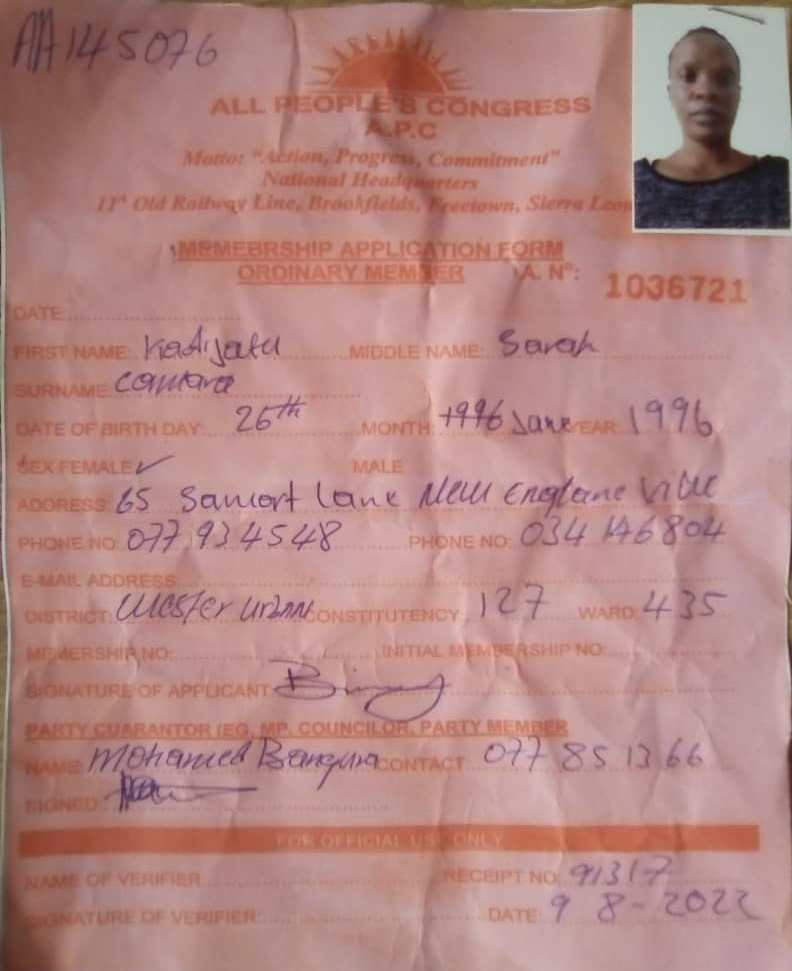

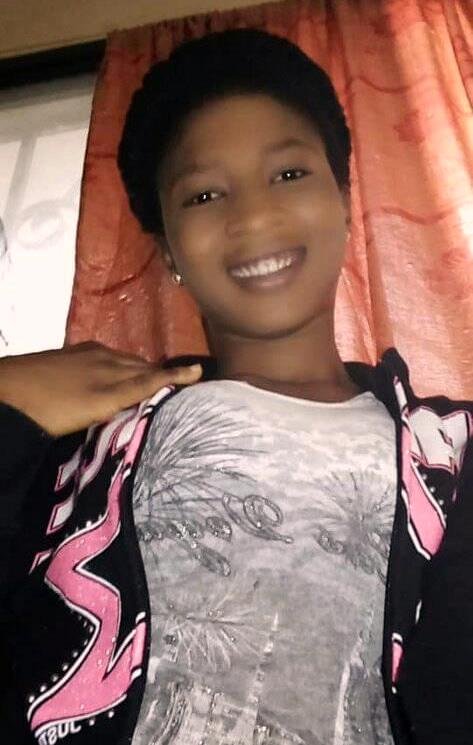

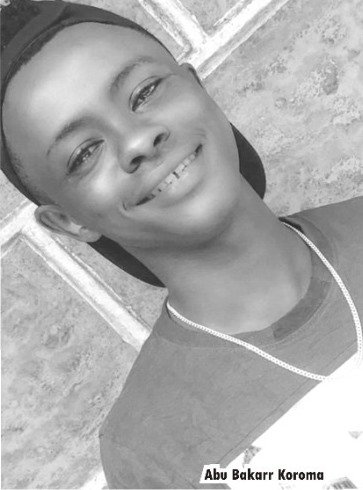

By Kadijatu Allieu

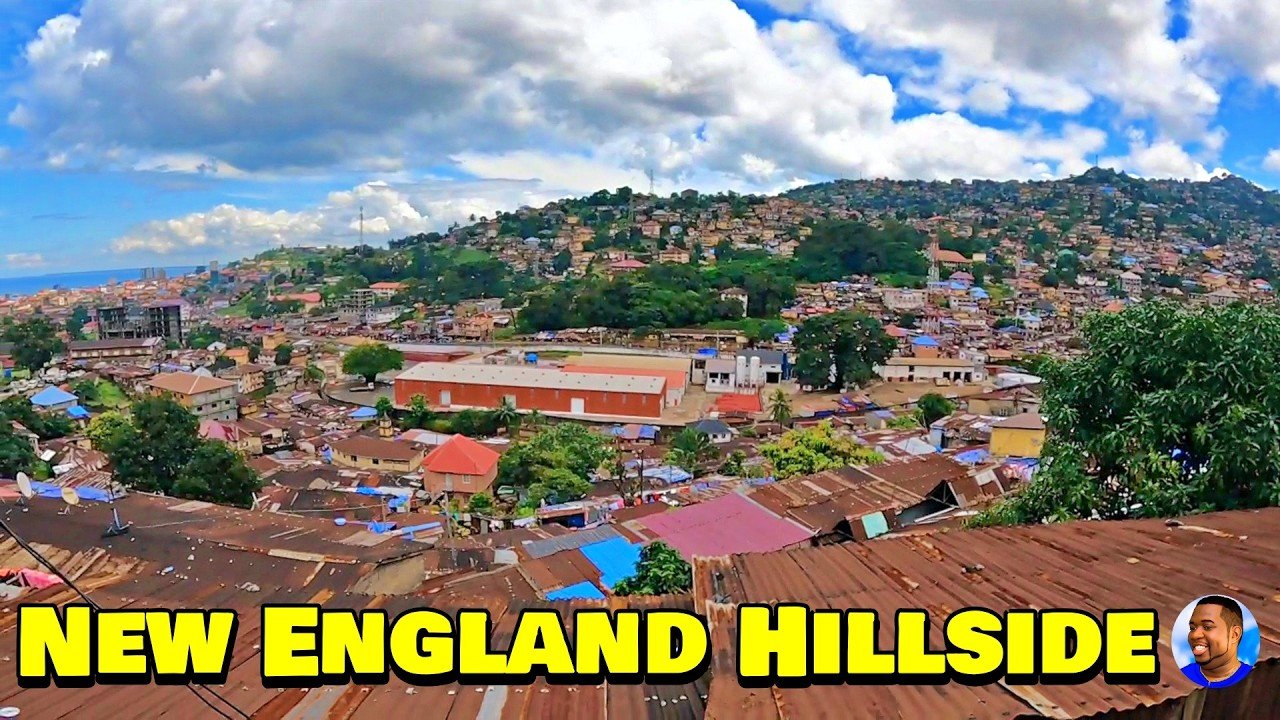

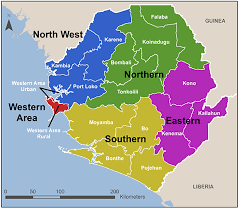

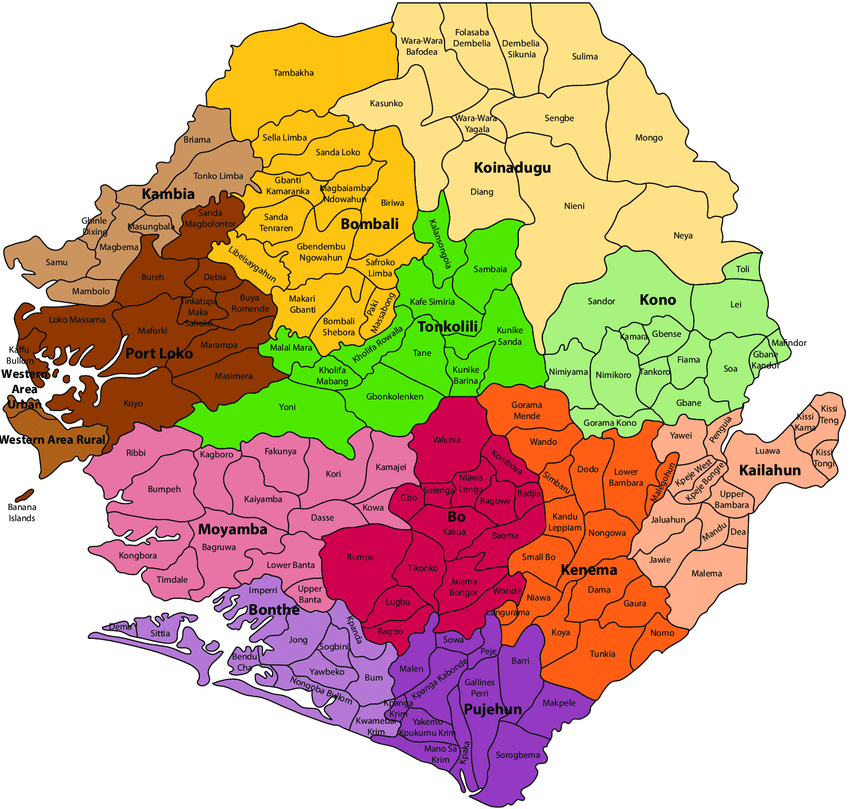

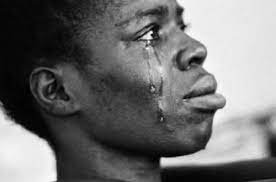

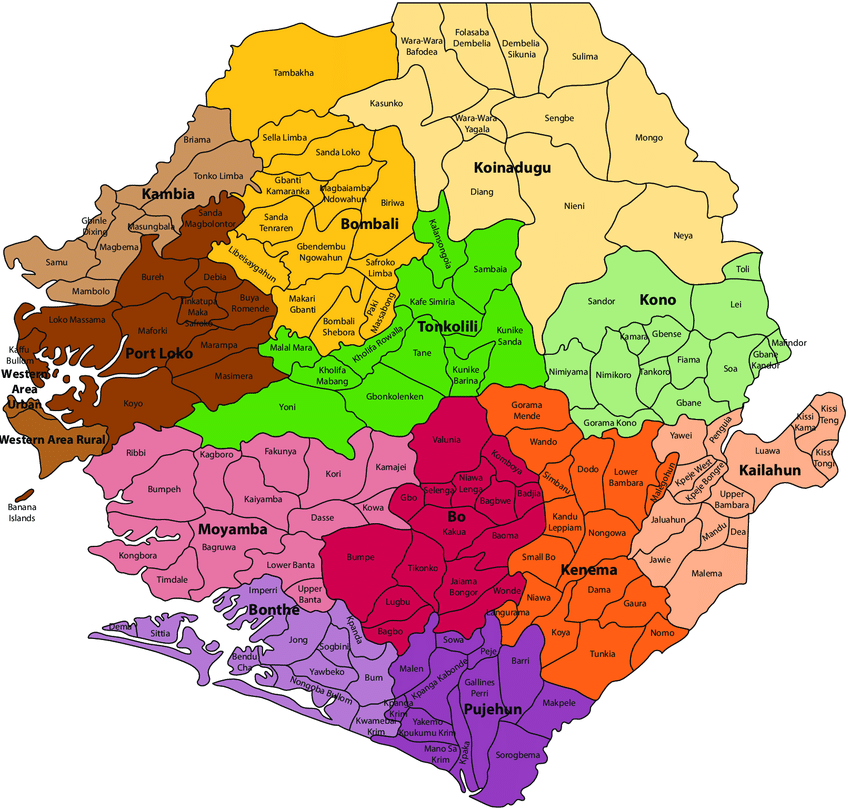

On a Friday in September 2016, in a small town in Kenema District, my life was changed forever. What began as a small argument over money turned into a nightmare.

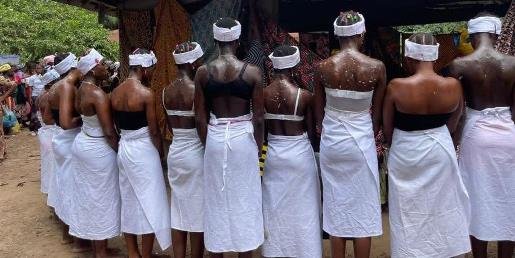

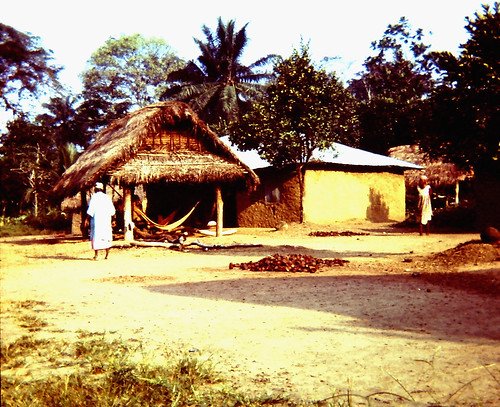

I went to my neighbour to follow up on money she owed me from osusu (the local savings group). The debt was more than two months overdue. Instead of answering, she insulted me. She spat on my brother’s name. She even called my mother a prostitute. It was clear that because I had not been cut, my neighbour believed my entire family was beneath her. I was humiliated, but I held my ground and reported the matter to an elderly neighbour, as I thought I should. She was leaving for Friday prayer, so she advised me to take my complaint to a sowei (female cutter), who was a respected figure in the town.

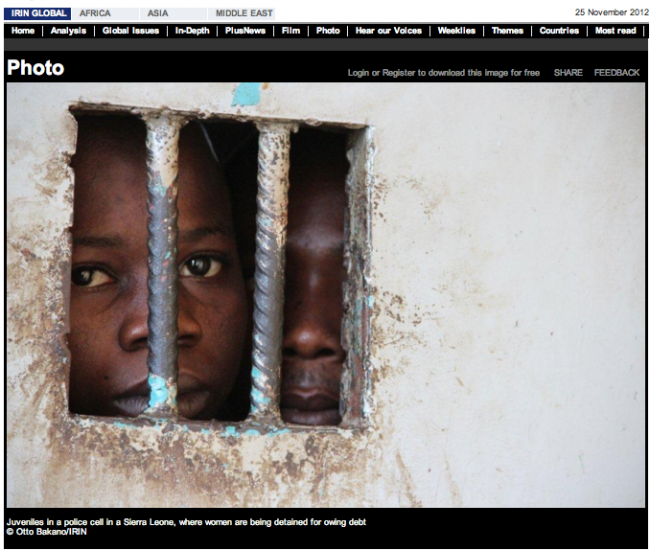

The sowei listened to my story about the debt. I left her place. About half an hour later, she sent for me. I had no idea I was walking straight into a trap. When I arrived at the sowei’s house, the neighbour I had been complaining about was there. The sowei asked us both to sit on the veranda, before taking us into a room where the windows and doors were closed. Then she demanded that my neighbour and I pay her a fine. I begged her, explaining that I had no money, that I had only come to explain my side of the dispute. But she insisted. Finally I managed to give her 10,000 leones, hoping the matter would end there. It did not. My neighbour, who was a cut woman, was allowed to leave after paying the exact same amount but the sowei kept me locked inside her house. It was as if she was offended that, as someone who had not been cut, I had “dared” to have a disagreement with a cut woman, and then “committed a further offense” by bringing the complaint to her. I cried, I pleaded, I prayed. I begged her to open the door. She looked me in the face and told me that nothing, not even God himself, could save me from what she had planned.

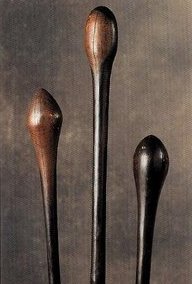

She covered my eyes with a black cloth, as up to six women came from inside the house and surrounded me. They took me into another room, pushed me to the ground and held down every part of my body: my hands, my chest, my legs. I fought but I was pinned. Then I felt a sharp object cutting my most private part. They mutilated me against my will. I bled and bled till there was a pool beneath my thighs. I screamed but no one came to help. There was no food, no water, no medicine. Just me, sliced open on a dirty floor, fighting for my life. They locked me in that house for three days and three nights. Luckily, I managed to get the woman guarding the door to go to my house and bring me my phone.

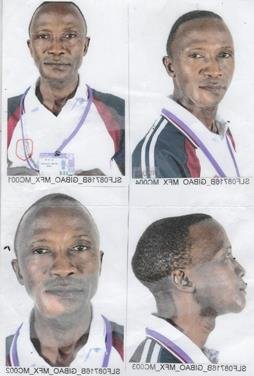

When I finally managed to send a message to a friend, the police and activists came to rescue me. They broke open a window to set me free and took me to the police station. The decision was made to take me to the local medical centre because I needed immediate medical attention before I could even give the witness statement. From there, I was sent to the district hospital, so I could be seen by a team of doctors. But even in the hospital I was not safe. The soweis sent threats. They promised to drag me back. Even when the then-Minister of Social Welfare was visiting me, they were not worried about punishment. They threatened to burn the hospital to the ground if I wasn’t handed over. I had to be disguised as a UN worker and smuggled, straight off

the operating table, across the border to Liberia for my own protection. I had to live there for years, begging for asylum. But I was told that since there was no longer a rebel war in Sierra Leone, I did not qualify for refugee status. They did not know that in this Sierra Leone it is not only in war that women are tortured.

I still live with the scars of what the soweis did to me. The medical complications have not gone away. But even worse is the emotional wound, the memory of being violated by women in my own community. What happened to me was not tradition. It was punishment. It was cruelty. It was a message: that a woman with a voice needs to be silenced with a blade.

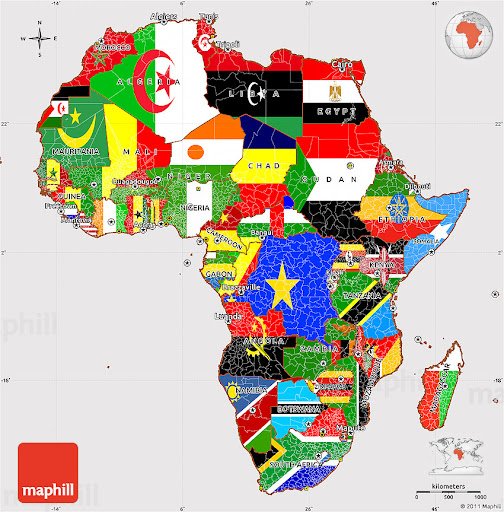

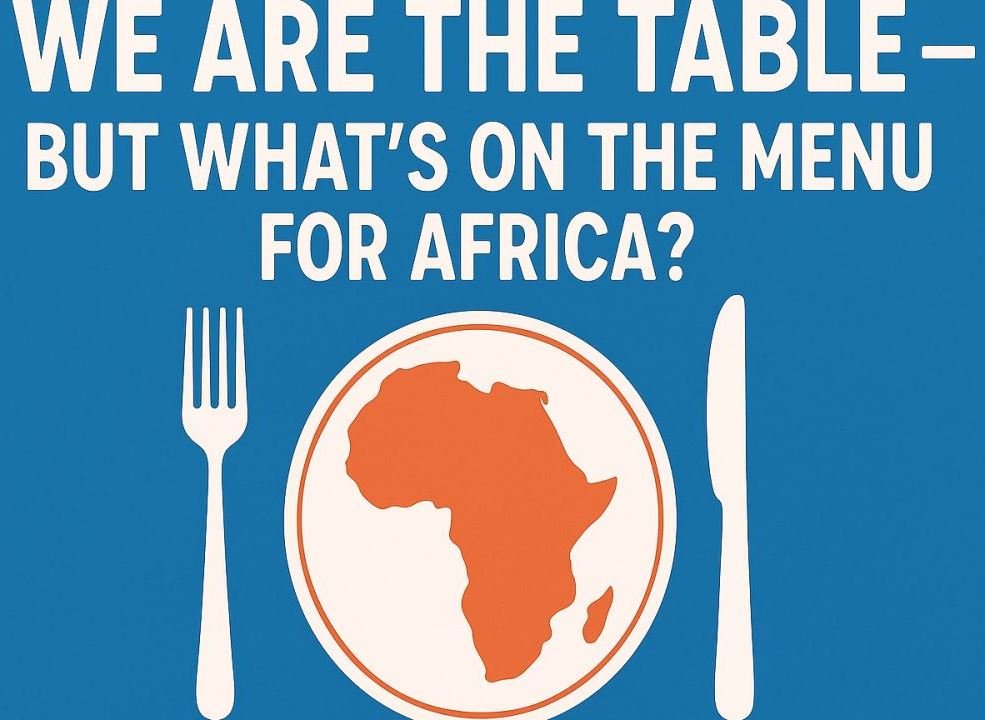

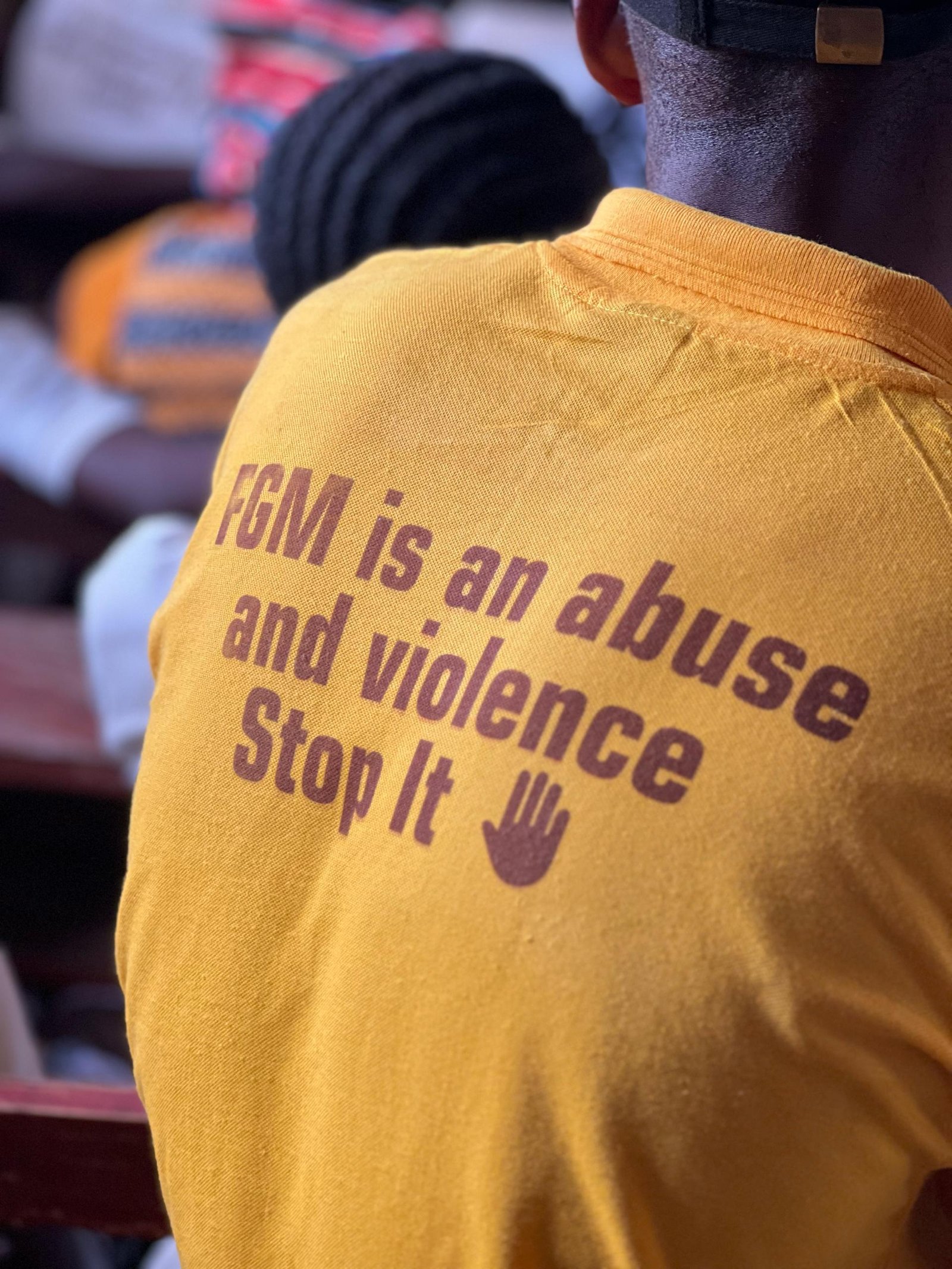

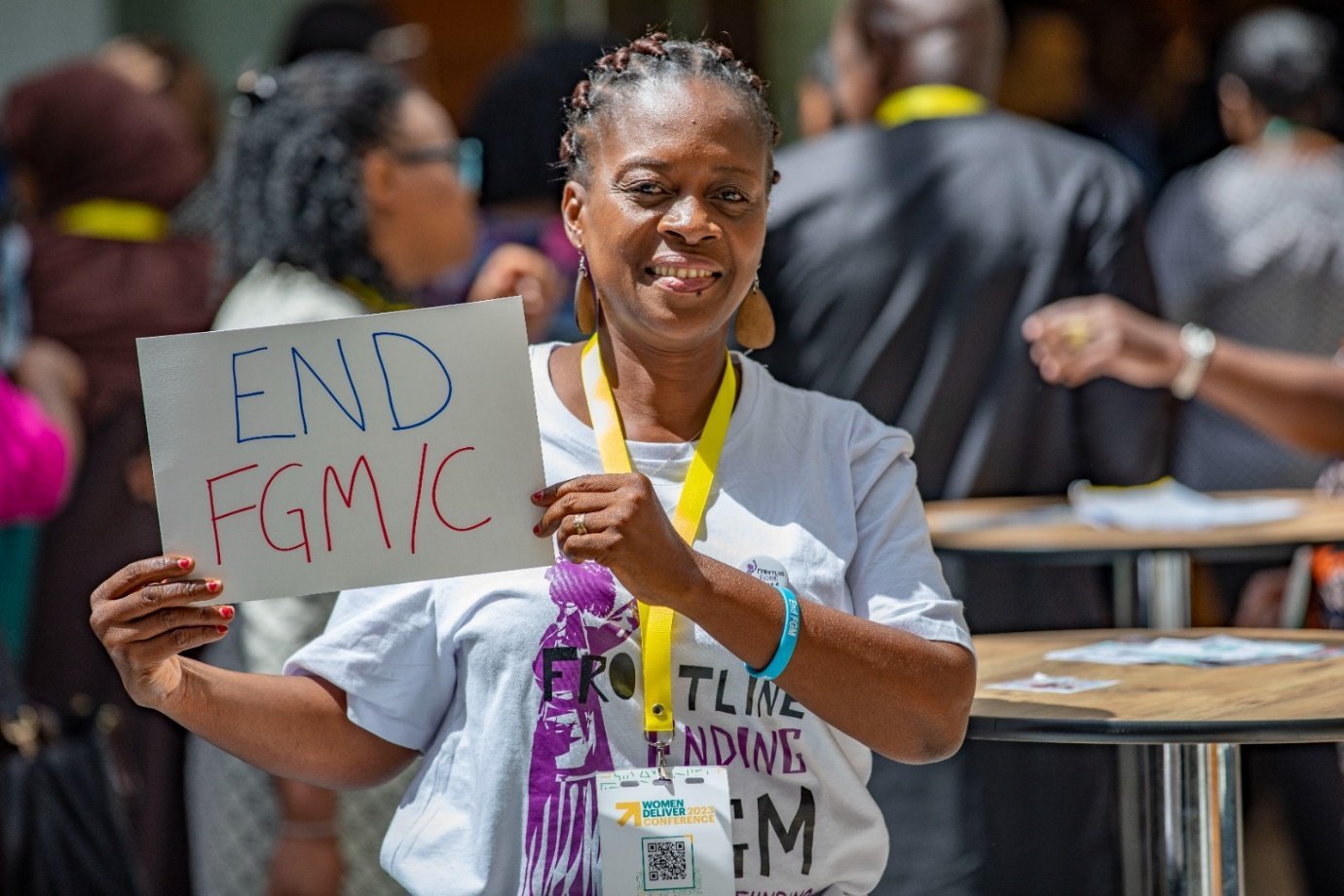

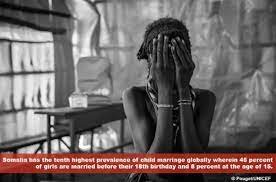

And here is the bitter truth: my story is not unusual. Sierra Leone has no clear laws that ban Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). A cruel system thrives. In many of the rural areas, those who are cut are honored, respected, and accepted. Those who are not are shamed, mocked, and pushed aside by those who are. The uncut are bullied into silence and treated like they don’t belong in society. And so, when we say that no Sierra Leonean female is pressured to be cut, and that everyone does it out of choice, we are simply not facing facts. Many women and girls go through Bondo simply to avoid being shunned, denied respect, called gborka, and tortured the way I was. They would rather bear the pain of the initiation bush with their peers than what I went through alone on the dirty floor of a stranger’s house.

FGM breeds injustice. Because they are protected by tradition, soweis think they are above the law. The women who cut me were not just wicked, they were bold! They told me to my face that no one would punish them for torturing me. If the government fails to act, it proves them right. And sends a message to the rest of the country that certain people are free to commit murder for any petty reason. That should terrify everyone. When crimes like this go unpunished, it does not stop with FGM. It creates a lawless society where the mad can roam freely. Just think about it: if people can hold down a woman, cut her, and just continue with their day, then who is truly safe?

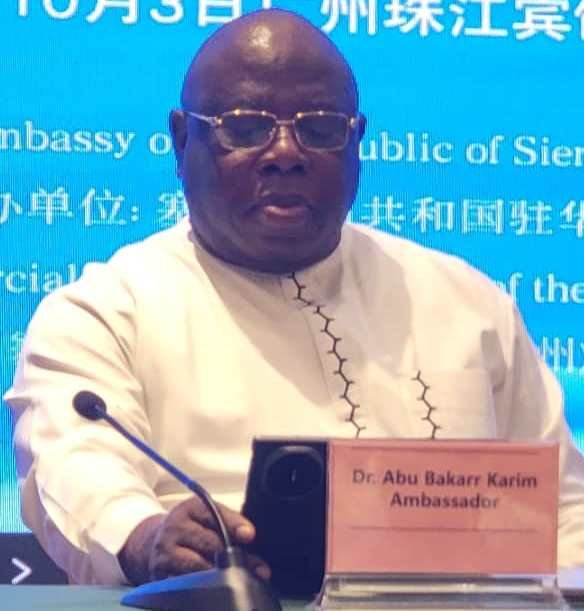

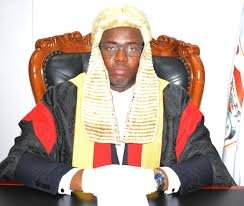

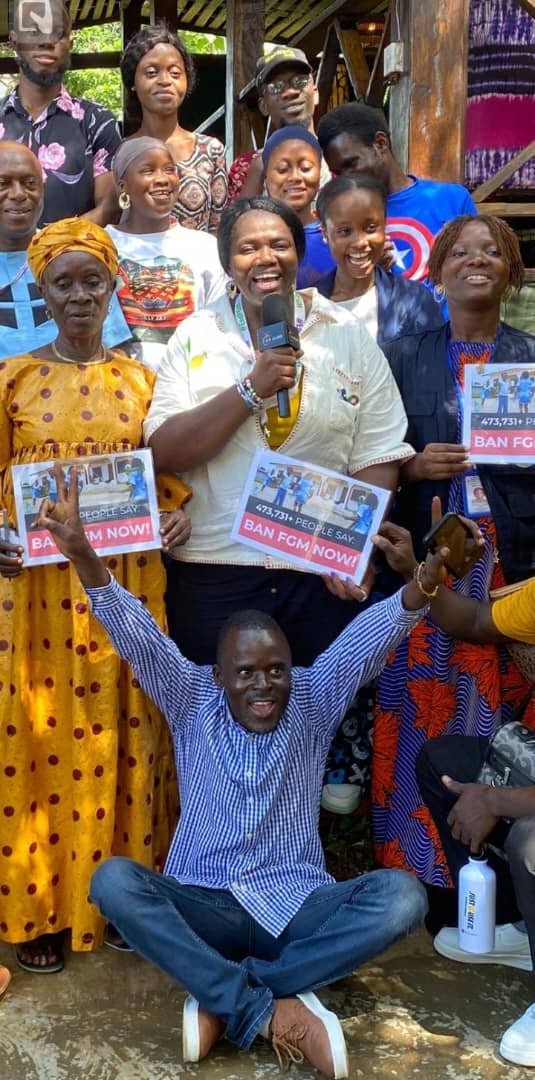

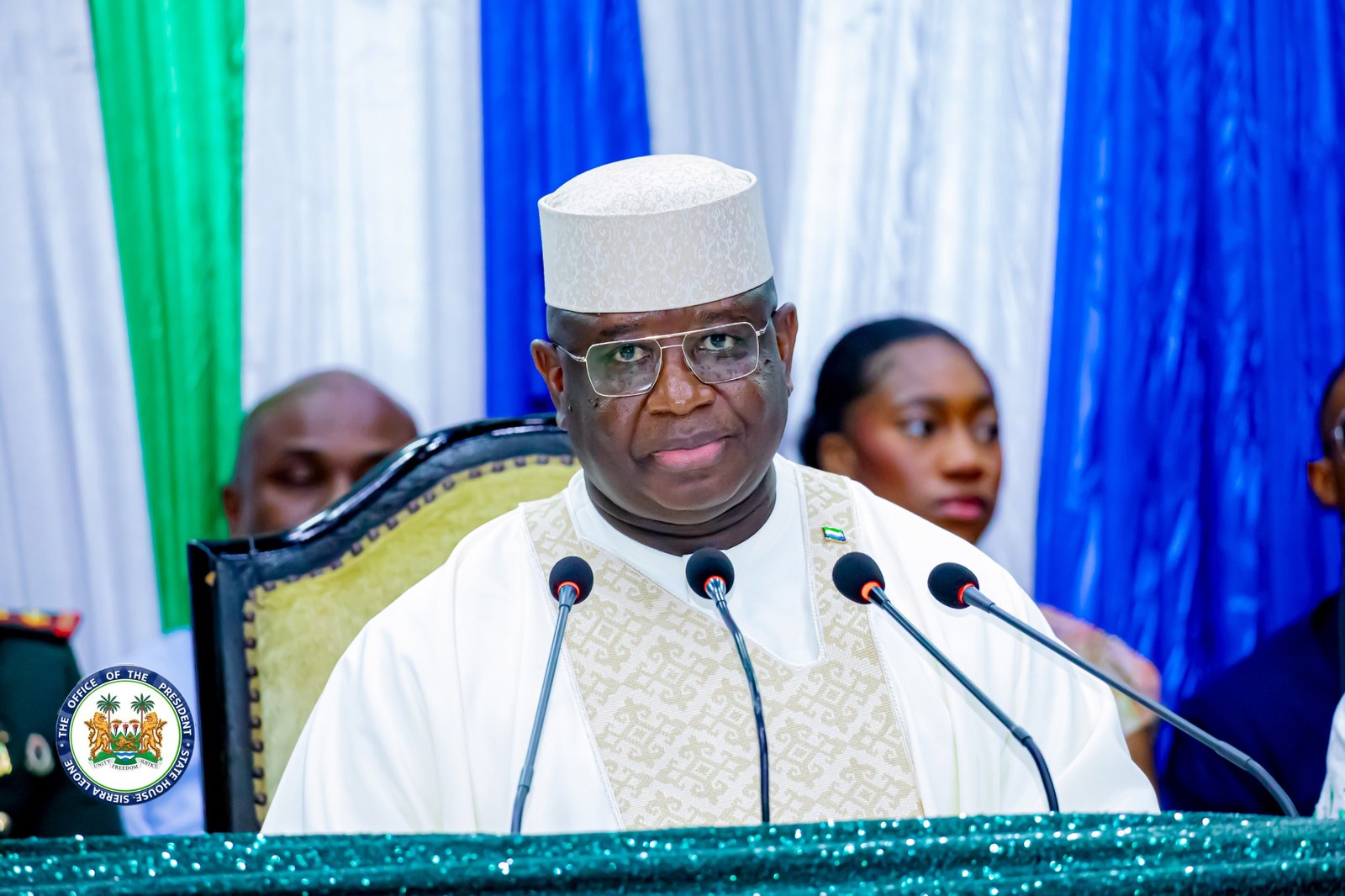

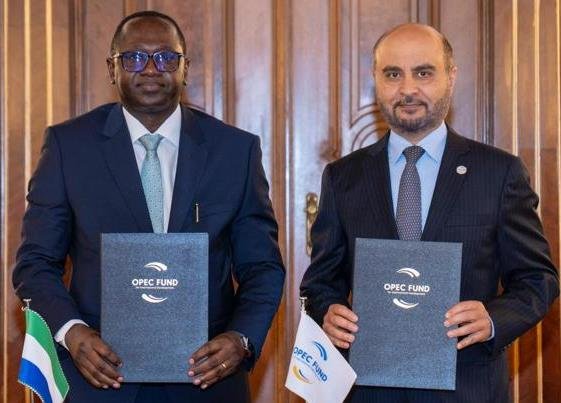

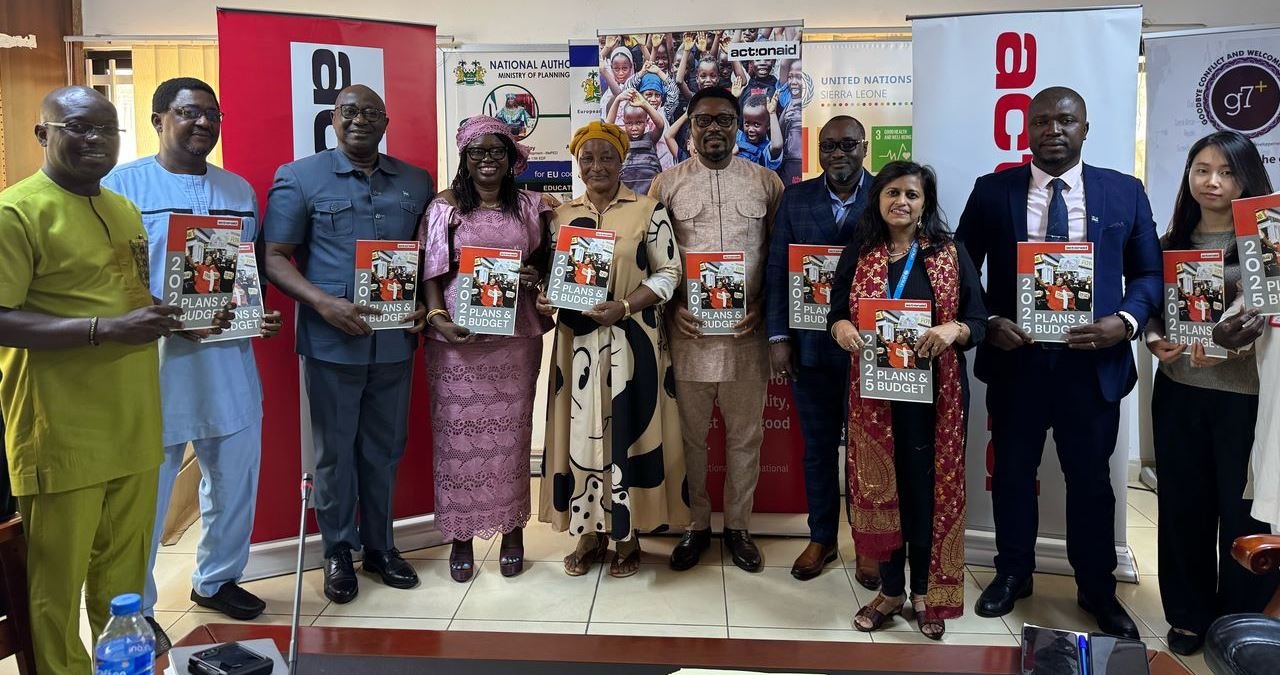

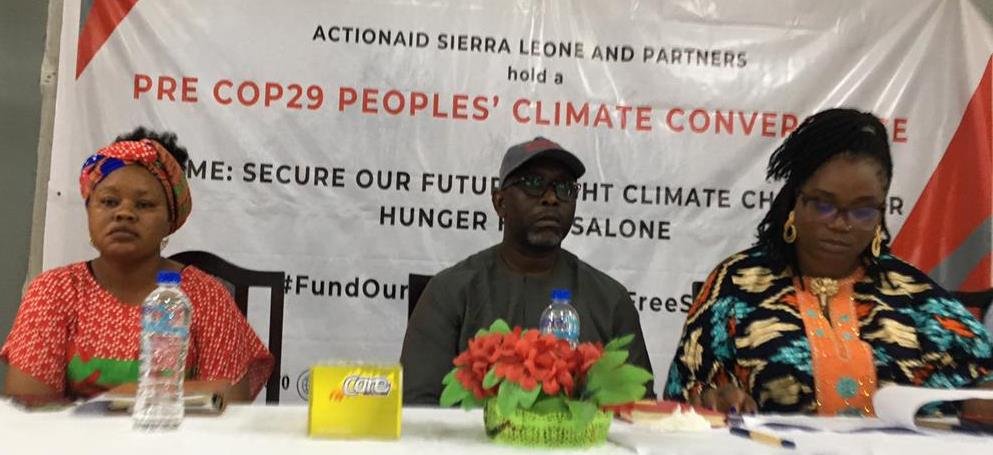

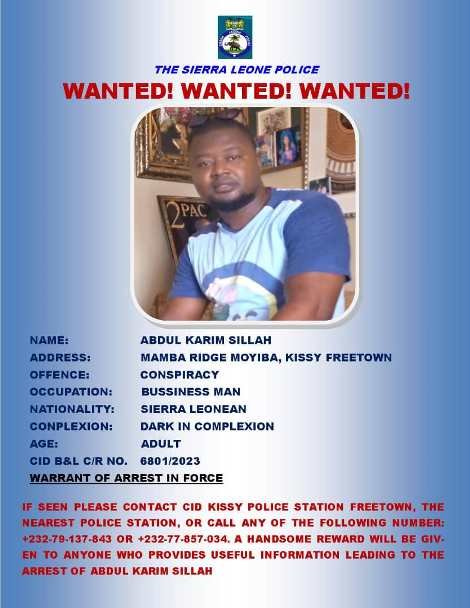

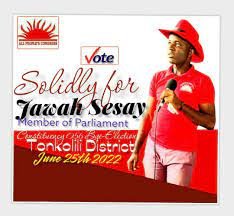

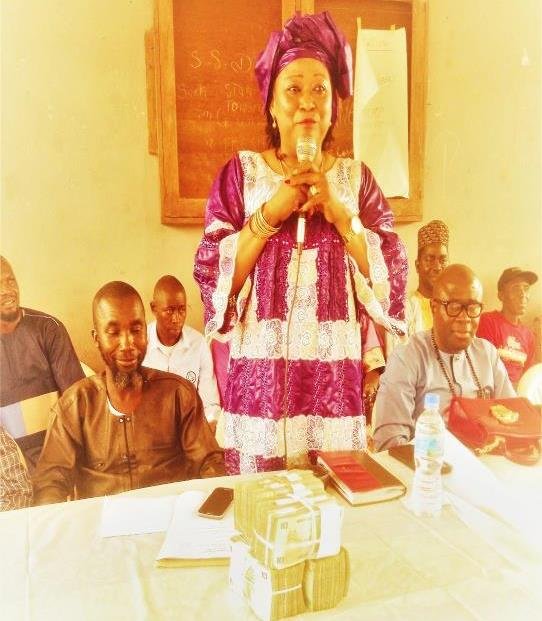

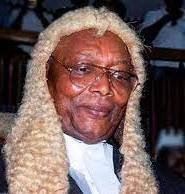

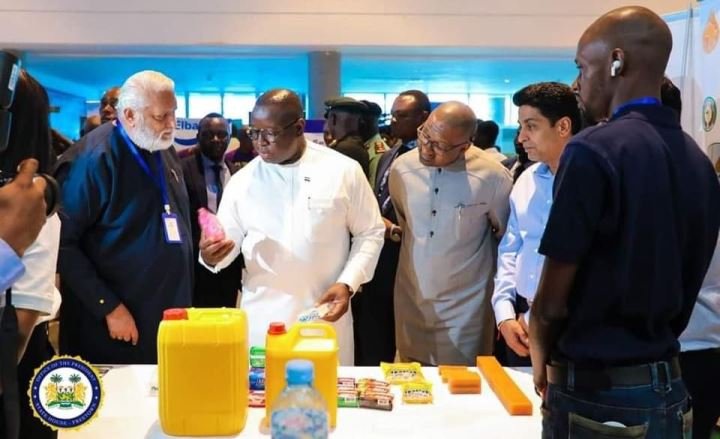

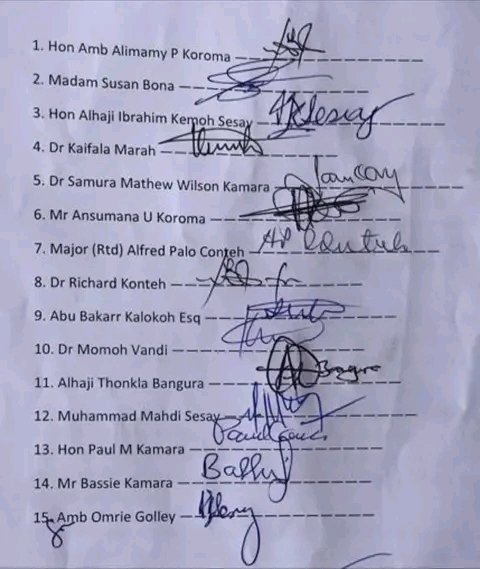

What happened to me destroyed my trust in my community but it did not break me. I fought for justice. The Forum Against Harmful Practices (FAHP) and Purposeful helped me file my case, both in the regional ECOWAS court and the local Sierra Leone magistrate court. On 8th July, 2025, I won the ECOWAS case. The court ruled that my rights were violated. The court said I should receive 30,000 USD in financial compensation, and that the Sierra Leonean government should investigate my attacker(s) and put them in prison. The ECOWAS court said that FGM should be banned by the government of Sierra Leone.

Now, on the ninth anniversary of my attack, I am ready to speak my truth anywhere in the world. Because what happened to me was a sin before God and man. I do not want pity, I want justice. My story shows that FGM is not harmless. It’s not a personal choice. It’s not a private matter. It is a weapon of torture. The world must see it for what it is.

This is not only my story. Thousands of women in Sierra Leone have faced the same. Many are broken in silence. Some have died. Others live with scars till they join their ancestors. Yet, the

soweis are chopping life, praised for protecting our culture. While survivors like me are suffering alone. I refuse to be alone anymore. I ask you to join me in this fight.

No woman should be tortured to “teach her a lesson.” No family should be forced to harm their daughters to save them from shame. No girl should be told she is nothing because she has not been cut. My dignity was stolen. But I still have my voice.

Sierra Leone needs a law that ends FGM. Survivors need justice. Communities need to learn how to do Bondo initiation without blood. Until that happens, I will never be quiet.